A Tale of two narratives?

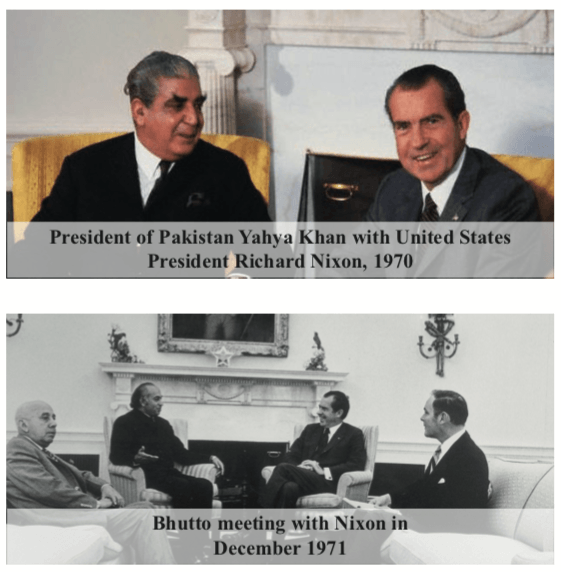

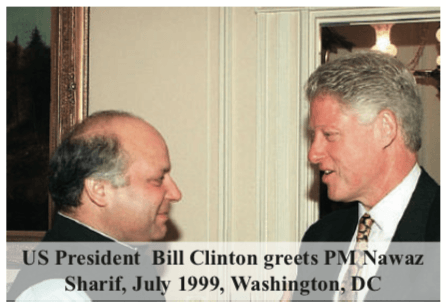

There are two narratives that have dominated U.S.-Pakistani relations over the decades. The first, well known to Pakistani audiences, is that the Americans use Pakistan when it’s convenient, and discard it afterwards – this reasoning goes that despite Ayub Khan’s loyalty in the 1950s, the Americans weren’t there when Pakistan fought its wars in the 1960s, culminating in the disastrous loss of East Pakistan (Bangladesh); that the Americans sought out Pakistani help after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, only to drop Pakistan and sanction it under the Pressler amendment when that war was won; that the Americans came back to the Pakistanis in 2001 and demanded assistance in the war on terror, which according to some experts led to Pakistani’s woes in public security today.

I heard this narrative from Pakistanis across the political spectrum when I served in Islamabad. Americans, many said, were hard-wired to let Pakistan down. Now, there’s a second narrative, well known to American audiences, that Pakistan takes American money, and then lies about what it’s doing. The arms and assistance given to Ayub Khan in the 1950s was not intended to be used against India, but that’s what Pakistan did, goes this account.

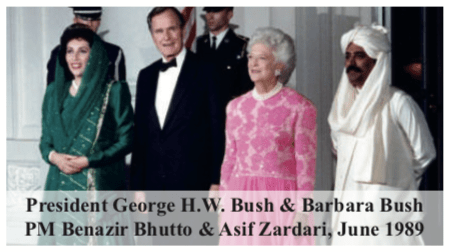

Bhutto cheated Americans about Nuclear Program

Despite efforts to remain friendly, relations deteriorated under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, who deceived the Americans about his nuclear program, a deception that was continued by his nemesis and successor, Zia ul-Haq. Even as the Americans then sought to make common cause against the Soviets in the 1980s, Zia continued with his nuclear aspirations, lying repeatedly to his American friends.

And then, when he was caught, the Americans had no choice under law but to sanction him and his successors who, almost alone in the world, supported the Taliban (who clearly were no friends of the U.S. and ultimately welcomed Al_Qaeda to Afghanistan).

Read More: Op-ed: The Future of Pakistan-US Transactional Relations

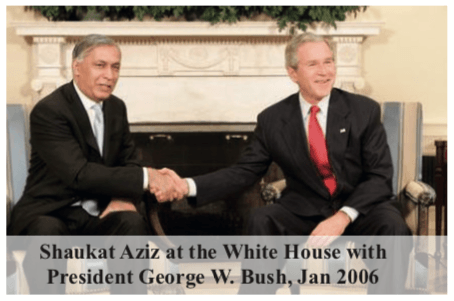

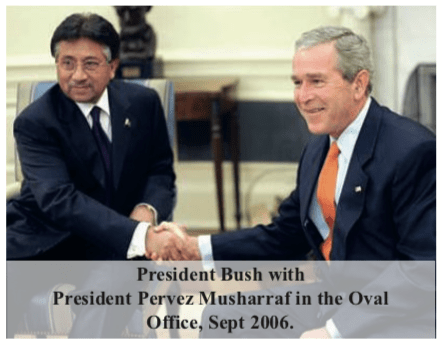

So by the time America came to Pervez Musharraf after the 9/11 attacks, the mistrust from the American side also ran deep and continued to do so as, during the 2000s, Pakistan continued to profess its commitment to counter-terrorist tasks while surreptitiously following its long-time practice of supporting domestic groups that engaged in terrorism abroad.

What will it take? Above all, I believe that for U.S.-Pakistani relations to improve, we will need a greater generosity of spirit on both sides, and a willingness to look beyond the artificial comfort of the two narratives we have about one another.

I heard this narrative when I first prepared to come to Islamabad, and it has only intensified; Pakistanis, many said, were hard-wired to betray America. Tendentious as these two narratives may be, there’s enough truth to both of them that experts – and publics – in both countries suffer from very deep mistrust.

This, to me, is all the more extraordinarily sad given the social and cultural affinity between so many Pakistanis and Americans on a day-to-day level, whether it be business leaders in both countries who see enormous opportunities to work together, or cultural figures in Karachi or Hollywood who enjoy the creativity and energy of each other, or tech geniuses in Silicon Valley who help power innovation and academics from both countries who have learned through scholarship and exchanges the talent and goodwill of one another.

Even the militaries of both countries, reputed to be at odds with one another so often, have a profound respect for the professionalism and dedication of their counterparts.

Read more: Imran Khan Worked his Charm Over Iran & Saudi Arabia: War Threats Clears

Winning Side of US-Pakistan Relations?

And I can attest to all of this, as I remember working with Pakistani army colonels to bring supplies to flood victims in Swat after the 2010 floods; I have talked at length with engineers and venture capitalists of Pakistani origin in Silicon Valley who dearly want to invest and work not only in Pakistan, but dream also about a broad, open South Asian market where they and their Indian-American colleagues could cooperate on world-beating technology and investment; I’ve visited artists in both countries who chafe and the restrictions they feel in their contact with one another; and I meet frequently with investors, entrepreneurs, and executives who have been successful in both countries, and shake their heads when they consider what they could achieve if relations at the political level were just a bit better.

But sadly, the two narratives dominate, and the underlying capacity for cooperation is still unexploited. In fact, in the time since I left Pakistan in 2012, I fear that the situation has gotten worse. The “Pakistan fatigue” in Washington is deeper and broader than I remember it, and many of my friends in Islamabad speak now of an era of Pakistani friendship with the Chinese that, despite the billions of dollars of U.S. assistance in the past, now looms as the outside source of capital and support.

I suggest that there are two big changes that need to take place before the U.S.-Pakistani relationship can make a fundamental improvement. No, I don’t mean a revival of the Holbrooke-era commitment to the creation of institutions that bring governments together and mobilize official U.S. government assistance under a new form of the Kerry-Lugar-Berman program.

I believe those days are over. We tried hard during the time of my ambassadorship in Islamabad, spending billions on training, education, public health, and energy, but the wholesale change in attitudes – essentially, the eradication of the two pernicious narratives I outlined at the outset of this article – have not changed. Rather, in order for the two societies, economies, and cultures of America and Pakistan to work together, I suggest that the two governments need to think hard about their approaches.

Read more: Riyadh-Tehran Tensions: Saudi Arabia to Work Closely with Pakistan

Challenge 1: Over-emphasis on American War against Terrorism?

First, from the American side, the preponderance of the counter-terrorism struggle needs to be balanced by empathy for the goals of those in the region (and not just Pakistanis). Yes, it’s axiomatic that any president since 9/11 must have as his or her fundamental goal the security from attack of the United States and its friends, and so the battle against terrorism must be fought with tenacity and determination.

But when America looks at Pakistan only through the lens of fighting terror, certain traits are magnified and others ignored; when America sees Pakistan simply as the place where terrorists who fight NATO troops in Afghanistan go to rest and reequip, then there’s a lot more attention to the Haqqani network and a lot less to the needs of the Pakistani people for water management, energy generation and distribution, and educational exchanges.

Yes, of course Pakistanis care about their personal security, but I suggest that they see this security as part of a broader question of how they live, their place in the region, and the development of their country. Thus from the American side, I would hope to see a greater understanding of what Pakistanis want.

Further, I would hope to see that the way Americans see this is not only through government-to-government relations, but through the soft power of American institutions, from universities to businesses to non-profits like the EastWest Institute where I now work, building with their Pakistani counterparts relations that can strengthen the long-term prospects for a democratic, prosperous, and tolerant Pakistan that could be at peace with its neighbors.

Read more: All the Claims of “Jew’s Agent” & Imran Khan wins “Muslim Man of the Year” Award

Challenge 2: Pakistani failure of Governance?

Second, from the Pakistani side, there is the glaring problem of governance. Americans want to support democratically elected leaders, despite what some Pakistanis say about a dark American preference for soldiers in charge.

Americans also want to support honest people who serve their constituencies; a parliament that distributes the burdens of paying for services fairly and equitably among citizens (for example, by paying taxes); an economy that fosters business leaders who in turn can be part of the political dialogue, as constituents rather than as recipients of patronage, rejuvenating and energizing the political parties so that they are truly representative of ideas about good governance that a well-educated electorate (yes, that costs money too, and we Americans would be wise to take heed of this as well for our own country too!) can vote for with civic pride rather than being relegated to the status of voter banks.

No country is without corruption. But corruption in Pakistan is exceptionally destructive and has held back the extraordinary potential of 200 million people at a time when countries all around Pakistan are taking advantage of the global economy even in difficult times. Even if they come to pass, these two changes – American vision beyond counter-terrorism, Pakistani reform of domestic governance – won’t solve all problems.

There will still be psychological issues between India and Pakistan, issues manifesting themselves in deep mistrust and holding both countries back from what should be their natural role as partners in prosperity.

Just as I have always maintained that Pakistan should not have to choose between two good friends, China and America, as both of them have plenty to offer, I also believe that America should not have to choose between India and Pakistan, who also have much to offer the United States.

I’m always sad to read, in the Pakistani press, the defensive and often poorly sourced accounts of Indian perfidy (and indeed, I’m always sad when I visit Delhi and hear prominent Indians tell me they simply wish Pakistan would go away).

Similarly, Pakistani relations with Afghanistan have had a number of opportunities in recent years, opportunities that have not been seized. I, for one, hope that the influx of Chinese capital in the Belt and Road Initiative might provide an impulse for cooperation between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

But the situation may simply have been too complex for too long to give us any easy solutions, and the tragic events of the last four decades, in which the Afghans above all have suffered extraordinary hardship and violence, may leave scars that are terribly difficult to heal.

Read more: Pakistan Facilitates Peace: Imran Khan seeks to mediates Between KSA & Iran

Way Forward?

What will it take? Above all, I believe that for U.S.-Pakistani relations to improve, we will need a greater generosity of spirit on both sides, and a willingness to look beyond the artificial comfort of the two narratives we have about one another. During my time in Pakistan, I met enough generous and tolerant people that I can always argue, in the United States, the heartfelt conviction that we share many qualities across cultures.

Similarly, those Pakistanis who have relatives in America or who have traveled here know of the openness and creativity that, even in times of political change like the present, are the characteristics of this culture.

And nowhere in my career as a diplomat was I treated with the warmth and hospitality I experienced in Pakistan – and this during a time that included Raymond Davis, Abbottabad, and Salala.

So despite the difficulties I describe here, I remain optimistic that Pakistan and America can do better with one another. It will take some of what the French call “civil courage” to make the changes necessary to work together constructively. I hope we’ll see that in the years and decades to come.

Dr. Cameron Munter is currently President of the EastWest Institute in New York, a private nonprofit organization that seeks to prevent conflict by building trust. He served as an American diplomat for three decades, across Europe, Middle East, Pakistan and Washington (he worked in the White House for presidents Clinton and Bush). He has a doctorate in history and has taught at Pomona College, Columbia University School of Law, and UCLA. He is currently a nonresident fellow at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and a member of the American Academy of Diplomacy. This article was first published, exclusively, in the Global Village Space Magazine (Dec. 2017 Issue), under the title: “US Pakistan Relations: Lens of an Optimist”