Dramatic Yacht Chase: Russian Man’s Wild Ride Ends in Beach Capture

New Mercedes SUV Faces Harsh Reality: Auction Bid Falls Short by $20K

What Makes a Car Feel Dated? Share Your Thoughts on Aging Automotive Features

Timeless Kitsch: A 1981 Chrysler Le Baron Town & Country Hits the Auction Block

Germany’s High Labor Costs Drive Automakers to Consider U.S. Production

Hilarious Tire Change: The Unexpected Twist in Mission: Impossible 2’s Motorcycle Chase

Hyundai i20 N: The Compact Hot Hatch That Delivers Thrills and Value

UK Car Exports Get Boost as Trump Cuts Tariff to 10% for First 100,000...

Tax applies to first 100,000 cars exported from UK to US; reduced from a previously announced 25% rate

Tax applies to first 100,000 cars exported from UK to US; reduced from a previously announced 25% rate

UK-made vehicles imported into the US will be hit with a reduced tariff of 10%, president Donald Trump has announced, but only for the first 100,000 cars exported.

It follows more than a month of negotiations between British and American officials after Trump announced sweeping import tariffs on foreign-made products, including a 25% tariff on new cars.

All tariffs were due to start on 1 April, but a 90-day reprieve was given so that negotiations could take place.

Details on the new deal are currently sparse, but the US confirmed that the 10% tariff - which brings it in line with the levy on other foreign goods – will apply to "100,000 cars", suggesting that anything over that number will be hit by the higher 25% rate. Previously, before Trump's March announcement, the tariff was 2.5%.

Prime minister Keir Starmer said the 10% rate represented "a huge and important reduction" and confirmed that "we have scope now to increase that quota; this is not final".

Last year, the UK sent some 102,000 cars to the US. The US is the British car industry's second largest export market, behind the EU. It received 27% of all UK-made vehicles in 2024, accounting for some £9 billion a year.

No details were given on the proposed 25% tariff on car parts, which was due to begin in the coming months.

While details have yet to be fully confirmed, new deals on food, chemicals, machinery and industry have been struck. Tariffs on steel and aluminum have been reduced to 0%.

The UK is the first nation to reach an agreement with the US following president Trump's tariff announcement in March. China will be the next, according to American officials.

Announcing the deal from the White House, Trump said: "I’m thrilled to announce a breakthrough trade deal. The agreement with one our closest and most cherished allies.

"Final details are being written up and will be detailed in the coming weeks."

He added that the deal gets rid of many unspecified UK tariffs that “unfairly discriminated” against US, saying: “They are opening up their country. Their current is a little closed."

Starmer said: "This is a really fantastic, historic day – a real tribute to the history we have of working together. This [deal] is going to boost trade."

In response to the news, Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders boss Mike Hawes said: "The agreement to reduce tariffs on UK car exports into the US is great news for the industry and consumers.

"The application of these tariffs was a severe and immediate threat to UK automotive exporters, so this deal will provide much needed relief, allowing both the industry and those that work in it to approach the future more positively."

The news marks a major step down from Trump's March announcement, when he signed a bill that penalised all car makers importing cars into the US market.

At the time, Trump said the decision was made because of the imbalance of American-made car sales in other markets and claimed the move would lead to "tremendous growth" for the US automotive industry.

Around eight million cars were imported into the US last year, approximately half the total sold in the market. Most were from Mexico, Canada, Germany and Japan.

The news will offer relief to the UK’s car makers, especially JLR (Jaguar Land Rover), which counts the US as its biggest market, having sent 130,000 cars there in 2024. It last month paused shipments to the US as it worked to “address the new trading terms”.

Speaking today, JLR CEO Adrian Mardell said: “The car industry is vital to the UK’s economic prosperity, sustaining 250,000 jobs. We warmly welcome this deal which brings greater certainty for our sector and the communities it supports.

"We would like to thank the UK and US Governments for agreeing this deal at pace and look forward to continued engagement over the coming months.”

Mini will also welcome the news, given that the Mini Cooper hatchback, which has recorded a near-doubling in US sales so far this year, is made at Oxford.

However, the Countryman SUV, made bigger in its most recent generation as part of a US market push, is made in Germany, which remains subject to the 25 tariff.

Tariff negotiations between the EU (of which Germany is a member) and US are still ongoing.

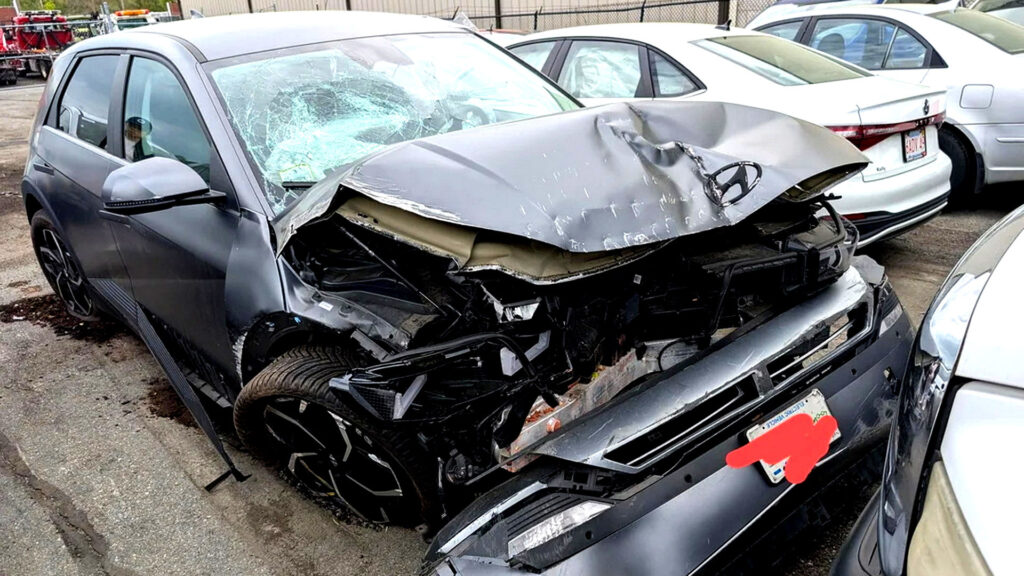

Unfortunate Turn: How a Hyundai Ioniq 5 Went from Repair to Total Loss in...

Unleashing the Future: Baltasar’s 500 HP Electric Track Car Redefines Performance