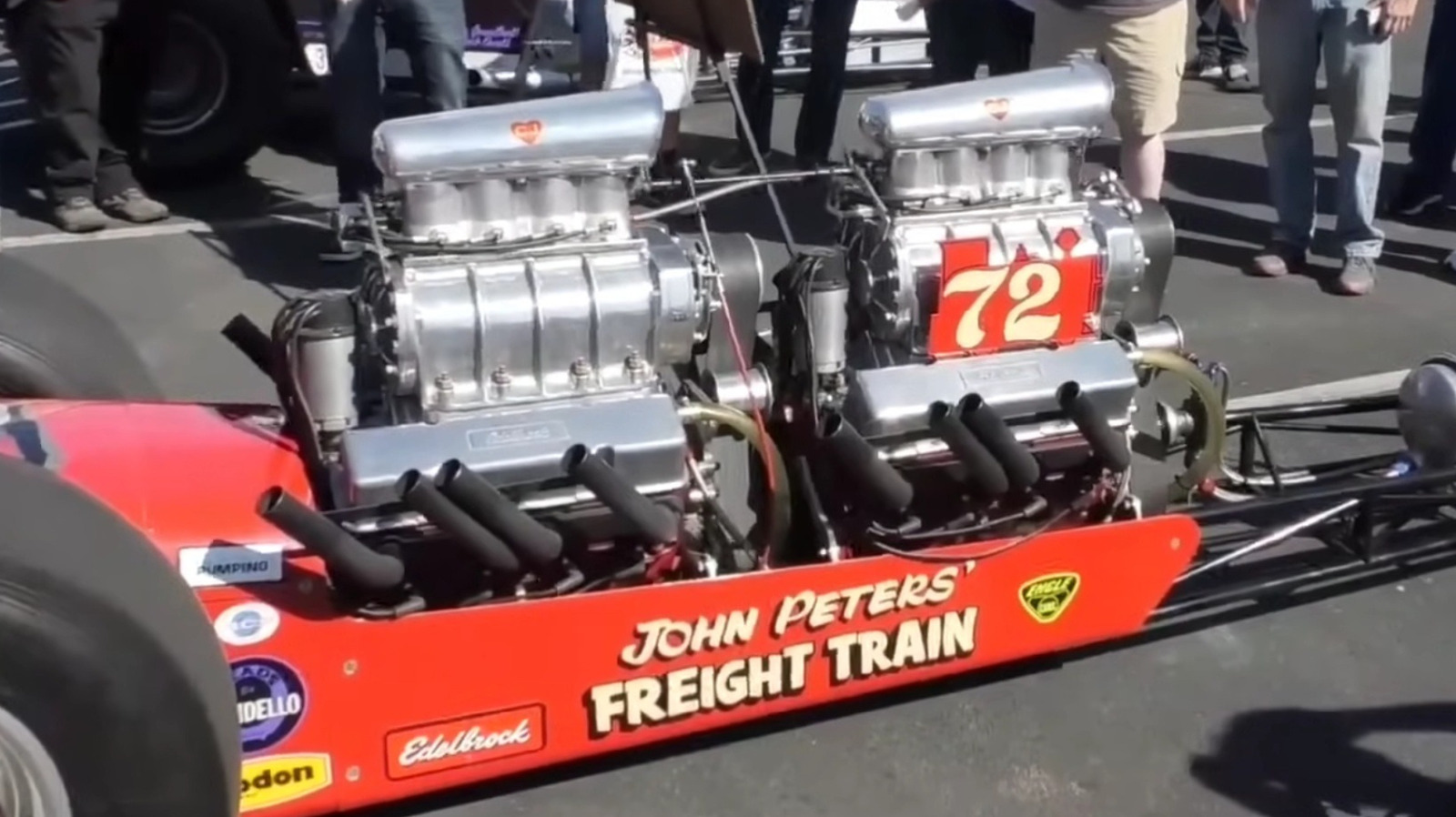

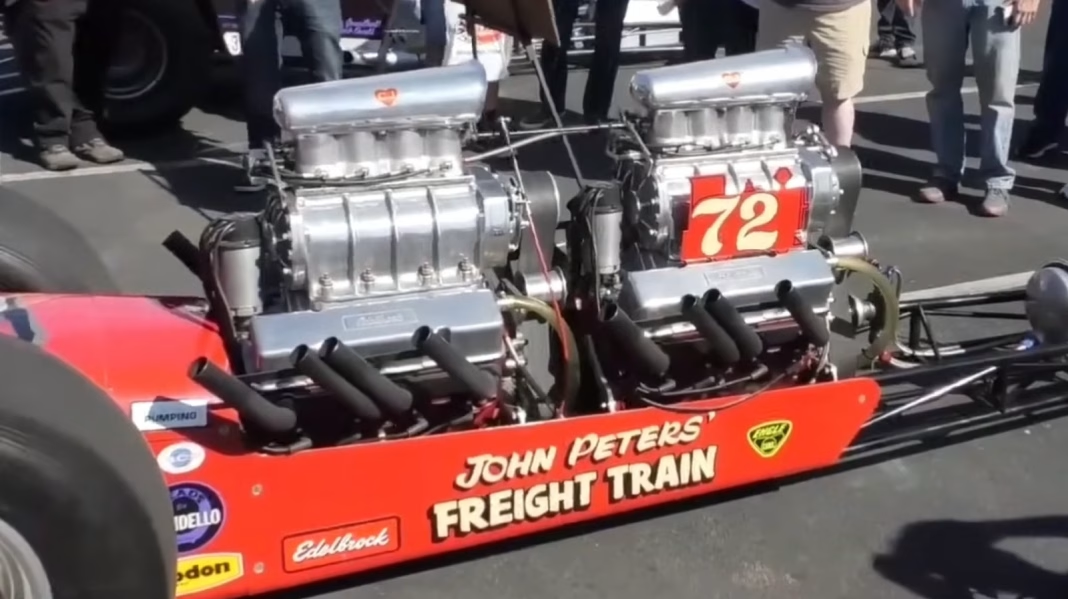

How Do Drag Racers Actually Fit Two Engines Into One Car?

If you’ve ever watched a drag race and spotted a car with not one, but two engines squeezed under the hood, you might’ve wondered—how on earth does that even work? It’s not just a wild idea from a gearhead’s fever dream. Twin-engine dragsters have a real history, especially in the world of Top Gas racing, where creative engineering was the name of the game.

Why Would Anyone Bolt Two Engines Together?

Let’s get right to the heart of it: speed. In the 1960s and 70s, Top Gas racers were constantly searching for ways to keep up with the nitro-burning monsters that dominated the strip. Gasoline engines just couldn’t match the explosive power of nitromethane, so racers started thinking outside the box. The solution? Double up on engines. If one engine couldn’t deliver enough horsepower, why not run two in tandem and combine their output?

It wasn’t just about raw power, either. Twin-engine setups allowed teams to experiment with weight distribution, torque delivery, and even reliability. If one engine faltered, the other could sometimes limp the car across the finish line—though, let’s be honest, that was more hope than strategy.

How Are Two Engines Connected to a Single Transmission?

This is where things get really interesting. There’s no single “right” way to bolt two engines together, and that’s what made this era of drag racing so innovative. Some teams mounted the engines side by side, while others stacked them inline, one behind the other. The real trick was figuring out how to synchronize both engines so their combined power could be fed into a single transmission and, ultimately, the rear wheels.

One popular method involved coupling the crankshafts directly with a custom-built shaft or gear system. This setup demanded precise alignment—any misstep, and you’d have a catastrophic failure at full throttle. Other racers used chain or belt drives to link the engines, which allowed for a bit of flexibility but introduced new challenges with slippage and durability.

Legendary builder Kent Fuller was known for his inline twin-engine dragsters, where both engines sat nose-to-tail and fed into a single clutch and transmission. The result? Pure magic. These cars could produce upwards of 1,200 horsepower—a staggering figure for the era.

What Were the Biggest Challenges With Twin-Engine Dragsters?

It wasn’t all checkered flags and champagne. Running two engines meant double the complexity. Synchronizing throttle response, ignition timing, and fuel delivery was a constant headache. If one engine ran even slightly out of sync with the other, you risked blowing up both.

Cooling was another major hurdle. Two engines generate a ton of heat, and keeping both within safe operating temperatures often required custom radiators and creative airflow solutions. And then there was the weight. Twin-engine cars were heavier, which could be a disadvantage off the line, especially if the extra power didn’t translate into enough traction.

Do Twin-Engine Setups Still Have a Place in Modern Drag Racing?

Today, you’re unlikely to see twin-engine cars at the top levels of professional drag racing. Advances in single-engine technology—think superchargers, turbochargers, and exotic fuels—have made it possible to extract insane amounts of power from just one motor. But the spirit of innovation that drove those early twin-engine builds is still alive and well.

You’ll still find twin-engine dragsters at nostalgia events and in the hands of passionate hobbyists who love the challenge and spectacle. It’s a nod to a time when rules were looser, and creativity was king.

What Can We Learn From the Twin-Engine Era?

The big takeaway? Chasing speed isn’t about perfection—it’s about smarter adjustments. Start with one change this week, and you’ll likely spot the difference by month’s end. Whether you’re wrenching on your own project car or just admiring the ingenuity of past racers, remember: sometimes the wildest ideas lead to the biggest breakthroughs.