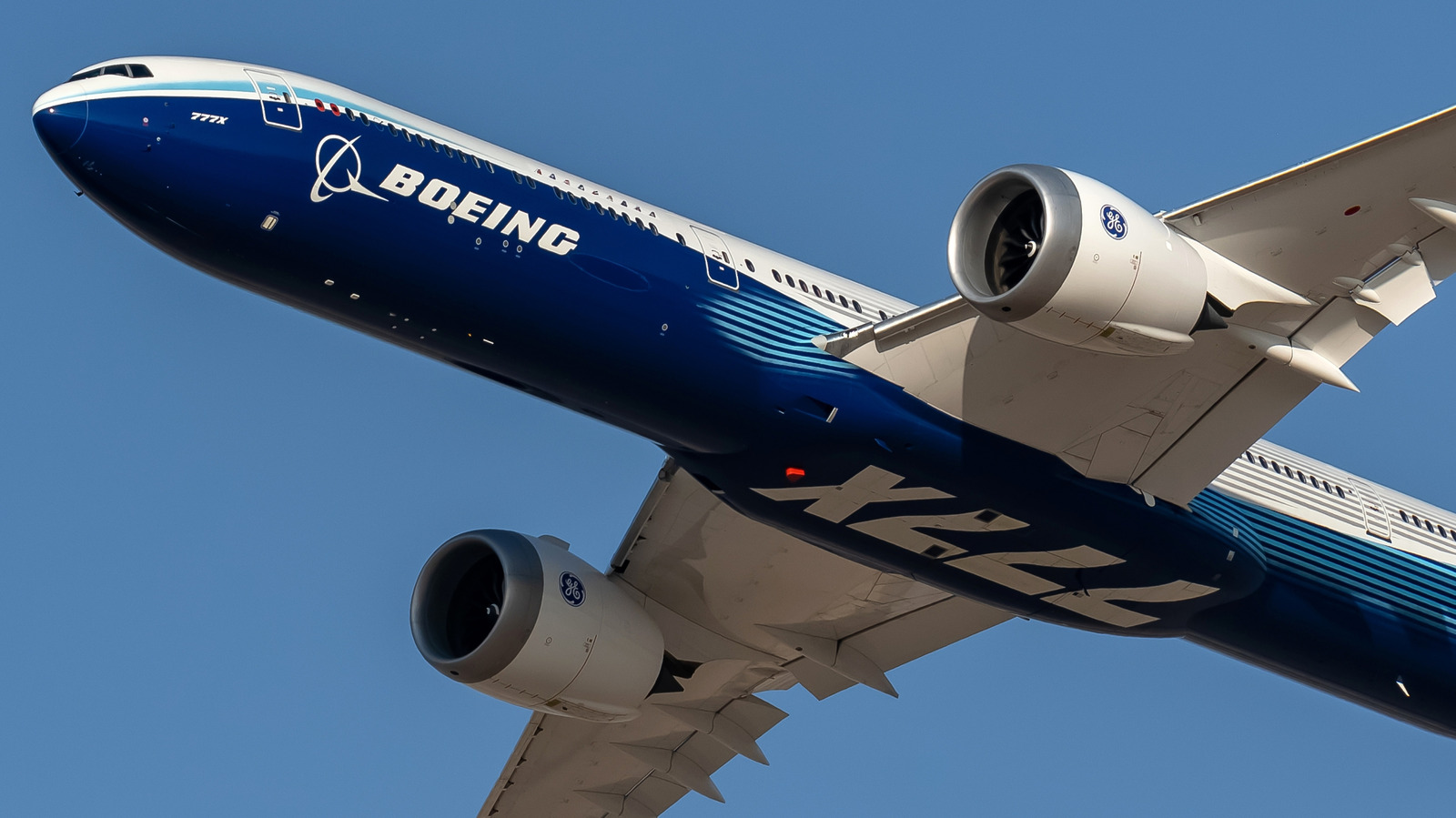

Who Actually Builds the Jet Engines for Boeing Aircraft?

If you’ve ever looked out the window of a Boeing jet and wondered who’s behind those roaring engines, you’re not alone. The answer isn’t as simple as one company. Boeing relies on a handful of powerhouse manufacturers—each with its own specialties, quirks, and global footprint. Let’s break down who’s who, which engines power which planes, and whether Airbus taps into the same pool of engine makers.

Which Companies Manufacture Jet Engines for Boeing?

Boeing doesn’t build its own jet engines. Instead, it sources them from four major players: General Electric (GE), Rolls-Royce, Pratt & Whitney, and CFM International (a joint venture between GE and Safran Aircraft Engines of France). Each brings decades of engineering know-how and a reputation for reliability.

General Electric is a giant in the aerospace world, known for its high-thrust, fuel-efficient engines. Rolls-Royce, with its British pedigree, is famed for smooth, quiet performance and cutting-edge technology. Pratt & Whitney, an American mainstay, has pioneered innovations like geared turbofan engines. And CFM International? It’s the world’s largest supplier of jet engines by volume, thanks to its workhorse CFM56 and LEAP families.

Which Boeing Planes Use Which Engines?

Boeing’s lineup is diverse, and so are the engine options. Here’s how it shakes out:

Boeing 737: The 737 family, including the latest 737 MAX, is powered exclusively by CFM International engines. The classic models use the CFM56, while the MAX series gets the newer, more efficient LEAP-1B.

Boeing 747: The legendary 747 has seen a mix. Earlier models (like the 747-100 and -200) offered Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, and GE options. The 747-400 mostly used the GE CF6, Pratt & Whitney PW4000, or Rolls-Royce RB211. The final 747-8 is powered solely by the GE GEnx-2B67.

Boeing 767: This versatile widebody can be fitted with either GE CF6 or Pratt & Whitney PW4000 engines.

Boeing 777: The original 777 offered a choice between GE90, Pratt & Whitney PW4000, or Rolls-Royce Trent 800 engines. But the latest 777X is GE-only, using the massive GE9X—the world’s largest and most powerful commercial jet engine.

Boeing 787 Dreamliner: Airlines can choose between the Rolls-Royce Trent 1000 and the GE GEnx-1B for the Dreamliner.

Boeing 757: Now out of production, the 757 used either the Rolls-Royce RB211 or Pratt & Whitney PW2000.

So, Boeing gives airlines some flexibility—at least on certain models. But for newer jets, the trend is toward exclusive engine partnerships, often for reasons of efficiency, certification, and streamlined maintenance.

Does Airbus Use the Same Engine Manufacturers?

Here’s where things get interesting. Airbus and Boeing are fierce rivals, but when it comes to engines, they often draw from the same well. Let’s look at the details:

Airbus A320 Family: The A320neo can be ordered with either the CFM International LEAP-1A or the Pratt & Whitney PW1100G-JM. The older A320ceo models use the CFM56 or the International Aero Engines V2500 (a consortium that includes Pratt & Whitney).

Airbus A330: This widebody can be fitted with either the Rolls-Royce Trent 700 or the GE CF6. Earlier versions also offered the Pratt & Whitney PW4000.

Airbus A350: The A350 is exclusively powered by the Rolls-Royce Trent XWB.

Airbus A380: The world’s largest passenger jet offers a choice between the Rolls-Royce Trent 900 and the Engine Alliance GP7200 (a joint venture between GE and Pratt & Whitney).

So yes, Airbus and Boeing both rely on GE, Rolls-Royce, and Pratt & Whitney for their engines. CFM International is also a major supplier for both, especially in the single-aisle market. The main difference? Some Airbus models have exclusive engine deals, while others let airlines choose.

Why Do Airlines Care Which Engines They Get?

It’s not just about horsepower. Airlines weigh a host of factors when picking engines: fuel efficiency, maintenance costs, reliability, noise, and even commonality with the rest of their fleet. For example, an airline that already operates a fleet of GE-powered planes might stick with GE to simplify training and spare parts logistics.

There’s also the matter of performance in specific environments. Some engines handle hot-and-high airports better, while others are optimized for long-haul efficiency. And let’s not forget the bottom line: According to a 2023 IATA report, fuel costs account for 24% of airline operating expenses, so a few percentage points of efficiency can mean millions in savings each year.

Are There Any Notable Differences in Engine Technology?

Absolutely. Each manufacturer has its own engineering philosophy. GE is known for pushing the envelope with composite materials and massive fan diameters (just look at the GE9X). Rolls-Royce leans into advanced aerodynamics and low-emissions tech. Pratt & Whitney’s geared turbofan is a game-changer for noise and fuel burn, using a reduction gearbox to let the fan and turbine spin at optimal speeds.

CFM International, meanwhile, has built a reputation for bulletproof reliability. Its CFM56 engine has logged more than one billion flight hours—a staggering figure that speaks to its ubiquity and durability.

What’s the Future of Jet Engines for Boeing and Airbus?

The next frontier is sustainability. Both Boeing and Airbus are pushing their engine suppliers to deliver lower emissions, better fuel efficiency, and compatibility with sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). GE and Safran are working on the CFM RISE program, targeting a 20% reduction in fuel consumption by the mid-2030s. Rolls-Royce is testing hydrogen combustion and hybrid-electric concepts. Pratt & Whitney is refining its geared turbofan for even greater efficiency.

The big takeaway? Choosing a jet engine isn’t about brand loyalty or chasing the latest tech for its own sake. It’s about finding the right fit for each airline’s unique needs—balancing performance, cost, and future-proofing. Start with one change this week, and you’ll likely spot the difference by month’s end.