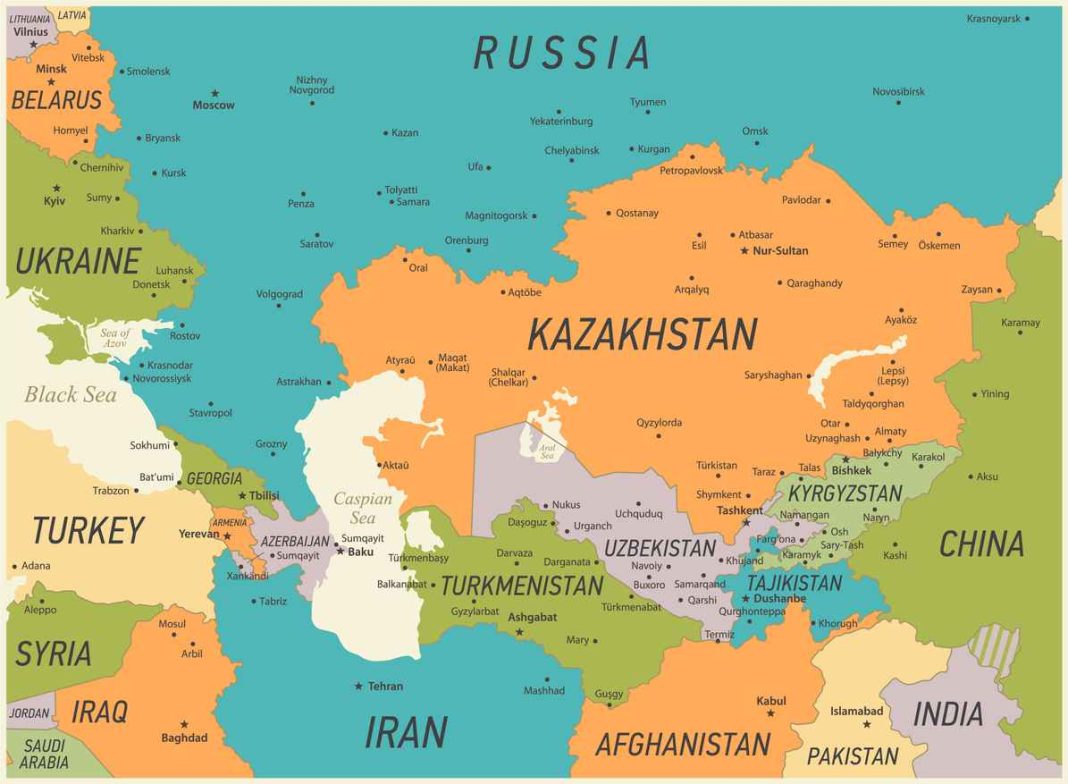

Ten years ago in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, the C5+1 format was launched—an ambitious diplomatic initiative linking the five Central Asian republics with the United States. Initially focused on regional security and development amid the U.S.-NATO counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, the platform has since matured into a strategic forum navigating great power competition, resource diplomacy, and connectivity.

This month’s tenth anniversary summit in Washington marked a turning point. Hosted at the White House, it signaled a shift “from diplomacy to deals,” with critical minerals, infrastructure corridors, and private-sector mobilization at the forefront. The U.S. aims to position Central Asia as a key node in global supply chains and energy transition strategies. Yet geopolitical tensions loom as China and Russia, once again, assess Western inroads into their traditional sphere of influence. Furthermore, Afghanistan, sharing over 2,300 km of borders with three Central Asian states, remains a wildcard—more stable, rich with shared water and other resources, yet diplomatically isolated, and nowadays, at odds over security concerns with its Eastern neighbor, Pakistan.

Immediately, in the footsteps of the Washington summit, as the Seventh Consultative Meeting of Central Asian Heads of State convened in Tashkent on Nov. 15, the C5 (plus Azerbaijan invited as a guest that became a full member transforming the group into C6) asserted regional agency through multilateral agreements and joint projects. Underscoring a shifting dynamic, China, Russia and Europe are also paying close attention to the region’s evolving significance.

Read more: A Republic of Relatives: Why Iran’s Rulers Still Stand

Beneath the summits and cooperation platforms lies a deeper imperative for the Central Asian stakeholders: peace and engagement with Afghanistan as a prerequisite for regional stability and economic integration. The path from Samarkand to Washington via Kabul – not to underestimate Beijing, Moscow and other trajectories – reflects a strategic recalibration already underway. However, the devil is in the details and in how rebalancing can avoid negative competition by aligning shared interests and promoting East-West synergy, or at least to prevent geopolitical collision.

From Isolation to Global Relevance

As part of the Soviet Union ruled from Moscow for more than 70 years, the five republics have each followed their own particular brand of de-sovietization post 1991. Normalization with the West occurred gradually and at varying speeds. After the EU summit in Central Asia, Washington is now stepping into a crowded and geopolitically charged neighborhood. Both the EU and the U.S. approach combined trade liberalization and investment with political reform incentives under initiatives like the Global Gateway and C5+1 (now C6+1).

The latter initially focused on regional security, economic growth and environmental sustainability. Now that Azerbaijan has officially joined the Consultative format, the Middle Corridor (also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route connecting China via Kazakhstan through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey to Europe) is key to unlocking the Central Asian republics’ path to growth, prosperity and stability.

Read more: Trump says Saudi prince ‘knew nothing’ about Jamal Khashoggi’s murder

Looking at the trajectory, during the last phase of Western military presence in Afghanistan, foundational dialogues emphasized on counterterrorism, border security and counter-narcotics. Covid-19 response coordination and medical aid boosted relations with key partners like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Post-Afghanistan strategy since 2021 has aimed to recalibrate regional priorities, with focus on stability and resilience.

Amid renewed Chinese and Russian influence, the region has been a key route for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Chinese investment in the region over the past 20 years has reached approximately $130 billion, primarily driven by infrastructure, energy and natural resources projects. Kazakhstan is by far the largest recipient (at more than 50%) while Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have attracted funds toward renewable energy, infrastructure and manufacturing. Since the BRI launch in 2013, cumulative Chinese engagement has reached $1.3 trillion globally (60% in construction contracts and the rest in non-financial investments).

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway now connects freight transport to Afghanistan. China launched a direct rail freight route from Chongqing to Hairatan in Northern Afghanistan this year. While the de facto authorities in Kabul stress on a balanced economy-centric foreign policy that is non discriminatory between East and West, they are left with few options when pressured by international sanctions and a cutoff from the banking system. Looking at new opportunities, they are eager for a Chinese decision to connect to Afghanistan by road, and later rail, via the high altitude Wakhan corridor.

Meanwhile, key Russian investments estimated at tens of billions of dollars continue to fund state-owned enterprises and energy companies in all five republics. The main Russian transport route South through Central Asia is the 7,200 km-long International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) linking Russian ports and cities to Iran, the Indian Ocean and the Gulf region with connections to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Western interest in Central Asia piqued again post 2022 as focus shifted to talks on minerals, supply chain diversification and infrastructure. Digital and climate initiatives were bolstered by business-focused initiatives, especially in logistics and technologies. The European Union’s Global Gateway flagship aims to mobilize up to 400 billion euros by 2027 to fund sustainable infrastructure and connectivity projects worldwide. EU leaders pledged 12 billion euros at the Central Asia Summit in Samarkand this year, aiming to connect the C5 to Europe. The recent summit in Washington accelerated the exchanges as Cold War-era trade restrictions were finally repealed by the U.S.

Summit Achievements and the Road Ahead

The C5+1 deliberations and the transactional Washington agenda this month have the potential to be a game changer if carried through in a sustainable and politically sensitive manner. Mindful of the China, Russia and Afghanistan realities, three sets of geopolitical and strategic themes were discussed and acted upon:

- Critical minerals and supply chains: The summit emphasized cooperation on raw materials, aiming to diversify supply chains away from China and Russia. Cognizant of the sensitivities involved, the Central Asians will need to come up with non provocative solutions.

- Security and regional stability: The U.S. highlighted the region’s strategic location and potential, referencing its Silk Road legacy and role in Eurasian connectivity. This option could offer a win-win outcome for all sides.

- Shift from diplomacy to deliverables: The summit marked a transition from broad diplomatic dialogue to concrete, trackable outcomes. Landlocked countries in Central Asia will have few options but to adopt a balanced approach to access, trade and deliverables.

While framed as a multilateral summit, the U.S. leaned into tailored bilateral engagements, especially with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Here is a breakdown of what was agreed to partially or in full:

=> With Kazakhstan, Air Astana signed a memorandum for up to 15 Boeing 787 Dreamliners, boosting its long-haul fleet. Kazakh President Tokayev met with U.S. executives to discuss the digital economy, innovation, and investment climate. The country is now positioned as a regional leader in logistics and mineral processing, especially within the new B5+1 business platform.

=> With Uzbekistan: Uzbekistan Airways converted previous Boeing options into firm orders. Also signed multiple bilateral agreements with U.S. firms in tech and infrastructure. President Mirziyoyev emphasized Uzbekistan’s openness to foreign investment and regional connectivity

=> With Tajikistan: Somon Air signed for up to 10 Boeing 737 MAX 8s and four Boeing 787-9s. Engaged in talks on energy and transport modernization with U.S. partners. President Rahmon highlighted its role in regional stability, especially in relation to Afghanistan.

=> With Turkmenistan: Focused on potential U.S. investment in gas and renewables, though no major deals were announced. Discussed transport corridors linking Central Asia to global markets. President Berdimuhamedov’s participation marked a rare high-level engagement with the U.S..

=> With Kyrgyzstan: Explored cooperation in agriculture, tourism, and education. Expressed interest in U.S. support for broadband and e-governance initiatives. Advocated for inclusive development across Central Asia.

The Afghanistan Conundrum: Risks and Opportunities

The summit indirectly addressed Afghanistan by reinforcing U.S. support for Central Asian sovereignty and regional stability, especially as Russia’s diplomatic recognition of the Taliban in October broke the UN-P5 informal consensus, reduced diplomatic initiatives and intensified competition for influence in the region. Russia’s recognition marked a major diplomatic shift, making it the first country to formally acknowledge the Islamic Emirate.

This move is part of Moscow’s broader strategy to expand its footprint in Central and South Asia through trade, infrastructure, and security cooperation. Afghanistan’s role as a potential transit hub for Central Asia was notably absent from summit deliverables, reflecting uncertainty over its political status and infrastructure reliability. Instead, the C5+1 states focused on alternative logistics corridors and mineral supply chains.

So far, short of having a well defined strategy or Afghan policy thus far, the U.S., by contrast, used the C5+1 summit to reaffirm its commitment to the sovereignty and independence of the five Central Asian republics, implicitly implying great power encroachment. Meanwhile, Washington has not commented much on tensions brewing between Kabul and Islamabad over security and counter terrorism issues that flared up last month resulting in a fragile ceasefire.

As a result, Afghanistan has responded by shifting key trade routes northward and westward, boosting cargo movement through Iran and Central Asia. The Central Asia–Afghanistan–Iran axis is gaining traction, with Afghanistan increasing use of Iran’s Chabahar port and Central Asian rail links. Air links have also reopened with India. This opens up multimodal corridors that bypass Pakistan for now, offering relatively reliable access to the Indian Ocean and Gulf markets. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are especially well-positioned to benefit from these developments, given their existing limited rail and road links to Afghanistan.

With Pakistan’s influence waning, Central Asian countries gain more diplomatic agency in shaping Afghanistan’s future. They can act as neutral brokers in regional dialogues, balancing ties with Russia, China, and the US. India’s direct outreach to the Taliban or via Central Asia further underscores the region’s rising importance.

As part of security and stability incentives, Central Asian states are considering deepening border security cooperation with Afghanistan to manage narcotics, migration, water usage and extremism. Joint infrastructure and trade projects may help stabilize northern Afghanistan, reducing volatility and fostering economic interdependence.

Kabul’s rulers would, however, need to be more sensitive to the security needs and concerns of all of their neighbors, making sure that they address key demands shared by many stakeholders regarding the formation of multi-ethnic consultative councils and enhancing governance inclusivity. The more pressing demand both inside and outside the country is still focused on lifting restrictions on girls’ access to secondary education and women employment to boost productivity and enhance livelihoods.

Shifting Geopolitical Dynamics

On the Moscow front, Russia has gone as far as offering military cooperation and intelligence sharing with Kabul regarding threats to its security and that of its Central Asian underbelly from various terror groups, especially ISKP which is now reported to have been displaced from Afghanistan and seeking new sanctuaries in Pakistan’s volatile Baluchistan province. Russia is also seeking to expand trade and infrastructure projects through Afghanistan, including energy corridors and Eurasian logistic networks.

Some analysts believe that both competing powers are vying to shape the region’s connectivity—Russia via Afghanistan, the U.S. via alternative corridors.

Iran, now once again pressured by Western powers, is asserting itself as an adaptable and resourceful regional player that cannot be easily disregarded. Its strategic importance continues to grow, as numerous trade routes and infrastructure linkages currently connect—or are poised to connect—through Iranian territory.

Meanwhile China is the bigger player with a deeper footprint that is also a major player with long-term goals and a more significant investment portfolio across the wider region stretching into Asia, Europe and Africa.

China regards the recent Summit hosted by Pres. Trump as part of a broader geopolitical competition with the US for access to strategic resources and influence in Eurasia, where China has heavily invested (some estimate more than $1.1 trillion in BRI) since 2013.

While maintaining a cautious stance, and avoiding committing large scale investments, China prioritizes stability and security cooperation to prevent militant threats to its borders. It also regards Afghanistan as a gateway linking South and Central Asia, and important for trade, transport and expanding regional infrastructure networks.

Afghan and Chinese activities in the mountainous Wakhan Corridor–where it shares a 92 km border with Afghanistan–signals long-term engagement. There is talk of building a road and later, perhaps, a rail link, security permitting. Chinese tourists and businessmen are often seen in Kabul. Meanwhile, Beijing plans to connect the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to Afghanistan despite tensions between the two neighbors.

These moves complicate U.S. efforts to shape regional norms or use Central Asia as a pressure point, as C5 states plus Afghanistan, will continue to hedge between powers. The U.S. military withdrawal (with the possible exception of partial U.S. control of Afghan air space) left a vacuum that regional actors—Pakistan, Iran, Russia, India and China—are trying to fill with divergent security and diplomatic priorities. As a result, coordination on counterterrorism is hampered by mistrust and lack of interoperability among regional forces. The Taliban government’s formal recognition remains elusive, despite growing ties and diplomatic presence with all neighboring states, in addition to India, Turkey, several Gulf countries and others. Recognition will be difficult to attain unless Taliban rulers in Kandahar agree to broaden governance, lift restrictions on girls education and women employment, and adhere to the country’s international commitments.

Power of Water Politics

But it’s not all about trade, railways and minerals either. Water is as important a commodity as any other in this part of the world. As in other water-stressed countries, with few exceptions, most of Central Asia is in need of water flowing from the mountains of Afghanistan and Tajikistan for a variety of purposes.

Today, as climate pressures intensify and development accelerates on both sides of the Amu River, the case for integrating the regions along the waterways has never been stronger. And the path to that integration begins with water. The real question is not whether Afghanistan should develop, but how to shape development jointly so the river can sustain all sides?

Central Asia’s cooperative models can be adopted by Afghanistan. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have shown how two neighbours can jointly manage a transboundary river through their collaboration for hydropower on the Zarafshan River. They operate hydropower together, exchange data openly, and plan through a basin council. Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan have signed a similar mechanism which generates energy and regulates seasonal flows for downstream agriculture. These experiences show that once countries share responsibility for a river, trust can be built alongside the benefits.

Agriculture is another arena where cooperation promises immediate gains. Uzbekistan’s policies on water-saving technologies offer a strong example. They subsidize drip, sprinkler systems, canal improvement, land levelling, efficient pumps, and even solar powered irrigation.

These investments reduce water losses while increasing yields. The same approach could be applied in northern provinces of Afghanistan, including in the area under the now expanding Qush Tepa canal. With financial support and technical guidance, Afghan farmers could modernize irrigation, reduce waste, and improve productivity.

A New Phase

The C5+1 summit and its resonance in Tashkent mark a decisive new chapter in Central Asia’s evolution. No longer a passive frontier, the region is emerging as a strategic actor in its own right. For the United States, the task ahead is to sustain this momentum—balancing competition with regional rivals while engaging connector states like Afghanistan carefully and in stages.

Central Asian powers are inherently linked by shared interests in long-term economic growth and integration, yet the stakes remain high and the window of opportunity is limited. Still, the path from Samarkand to Washington—perhaps at some point passing through Kabul—illustrates that strategic alignment is not only conceivable but already taking shape, even as others recalibrate their approaches.

Omar SAMAD is a former Afghan Ambassador to France and Canada, Government spokesperson, and Senior Advisor to the Chief Executive. He is a facilitator for and member of dialogue processes; CEO of Silkroad Consulting, with current and past think tank experiences (Atlantic Council, USIP, and New America).

The opinions presented here reflect the author’s personal analysis and experience, which may not fully align with the publication’s editorial outlook.