Caterham Seven 310 Encore Bids Farewell to the Beloved Ford Sigma Engine with Limited...

New Seven 310 Encore is the last to use the fantastic 1.6-litre Ford Sigma engine

New Seven 310 Encore is the last to use the fantastic 1.6-litre Ford Sigma engine

You might have heard that Caterham has found a new engine supplier in Horse (decent name, I think), a joint venture between Renault and Geely.

Horse engines will go into Caterham’s Academy racing cars (which I have driven) from next year to replace the Ford 1.6-litre Sigma engine, which Ford hasn’t made in years. Caterham has been assembling race car engines from a stock of blocks and bought-in parts and stopped using it in road cars some time ago.

The Sigma is a nice engine. Autocar had one in a 140bhp Supersport long-termer that we ran in 2012-13, and I spent a lot of time in it, including an edifying day at Rye House kart circuit to see whether any car could have the handling of a go-kart. The answer was no, of course, but still, I remember it as one of the best driving days of my life.

The Sigma is lighter than the Ford 2.0-litre Duratec engine (which Ford doesn’t make any more either) that Caterham now uses in most of its road cars, and it has considerably more power than the kei car-compliant 660cc Suzuki-engined 170. But with the arrival of the Horse engine, the Sigma is finally on its way out.

To mark its run-out, Caterham has announced a special-edition road car, the 310 Encore. The engine is tweaked to 152bhp at 7000rpm, plus you get a lightened flywheel and sports suspension. There are some other upgrades too, there will only be 25 of them and they will cost £39,995.

Of late I’ve said that my favourite Sevens are the 170 and the 620, the extremes at either end of the scale, but this Encore car might just sit in a sweet spot reminiscent of that old Supersport.

If you’re looking for a Goldilocks Seven, this could be it.

Twisted TBug Reinvents the Classic Baja Bug with Charm and Custom Style

The Twisted TBug is yet another rear-engined, air-cooled resto-mod - but it's different in all the right ways

The Twisted TBug is yet another rear-engined, air-cooled resto-mod - but it's different in all the right ways

Have you seen the Twisted TBug? Twisted, the friendly, Yorkshire-based modifier of classic Land Rover Defenders (and now owner of a marine division as well), has started offering a Volkswagen Beetle Baja Bug restomod too.

(If it starts doing Hillman Imps, our respective garages will look even more alike.)

Unsurprisingly, the TBug looks somewhat nicer than my Baja Bug, because Twisted are people who are used to doing things properly. The interior looks trimmed beautifully, the stance is just so (I’m tempted to have a word with the front end of mine and a grinder) and there’s a reinforced chassis, a new engine, new electrics and LED lights that don’t look daft.

The power output has been about doubled over the original, but it’s still making less than 80bhp, so it isn’t a fast car – but that doesn’t matter a bit. “What makes the TBug special is that it makes you smile every time you slide behind the wheel,” says Twisted founder Charles Fawcett.

“In a world of increasingly serious and complex vehicles, there’s something wonderfully refreshing about that.” As they might have said in the 1970s, I can dig that.

Unlike Twisted Defenders and Suzuki Jimnys, this car exists in the ‘special projects’ bit of the company’s offerings. Lots of personalisation and customisation is on offer and it’s the sort of thing you could get lost for days in with the designers – although Twisted has made three for sale already to its thinking, in grey, green and yellow. You can spend around £95,000.

Rather refreshingly, the TBug is a restomod that isn’t about adding silly power, keying a chassis down to the road or fitting an electric drivetrain to it. And better still, it’s one that’s based on a rear-engined, air-cooled, two-door German car but not a you-know-what.

Why Bold Grilles Still Matter The Enduring Power of Car Faces in Automotive Design

Massive grilles are not just a modern trend - and if done right they can give a car real personality

Massive grilles are not just a modern trend - and if done right they can give a car real personality

I think it was the Americans who started it. When I was a little kid, the Detroiters were heavily into indulging themselves with some of the most massive, chrome-laden, over-the-top front grilles in history, and I loved them all, even though I usually only saw them in pictures.

At the time, an elaborate grille usually went with a chest-high set of tin tailfins overhanging the bootlid of practically every full-sized American car (and quite a few British and mainland European offerings too), but I never cared as much about them as I did the grilles: they didn’t have the same high purpose.

Distinctive frontal façades did two things for me – and still do. First, they did a perfect job of defining a car’s make. A Chevy was very different from a Ford, despite equal ironmongery.

Second, they spelled out the prevailing mood of the society from which they sprang. Back in the ‘chrome grin’ era, the pervading mood was optimism and anticipated prosperity: the end of war, a gradual freedom from austerity, the beginning of a baby boom, an increase in personal ambition and very little concern about economy or efficiency.

Now it’s very different. I love the way that grilles have changed through the ages, keeping their role as a guide to the times. Compare the joyous exuberance of an early Cadillac Eldorado with the efficiency-driven restraint of 2020’s Volkswagen ID 3, for example.

It’s amazing to me that while absorbing such seismic design shifts, grilles can still maintain a marque’s historical connections.

Today, I get special pleasure from the seven-slat grille of a Jeep Wrangler, re-expressed over many years by hundreds of designers intent on maintaining a connection to the ubiquitous wartime 1940s Jeep – whose original radiator shroud simply had a few casually cut vent slots.

I’m also intrigued by how the grille designer’s challenge gets ever greater. Today’s electric cars don’t strictly need grilles at all, but car companies that want to be successful still see a vital need for them.

Witness Jaguar’s new Type 00 concept, which keeps a long nose and a carefully designed frontal facade, even though it doesn’t strictly need either.

The fascination of the future will be seeing how things proceed, given that more and more car models crowd the world market.

Great surfaces, harmonious shapes, ideal proportions and a perfect stance are all fine, but providing 2040’s cars with distinctive faces looks like posing a whole new problem.

Twisted TBug Reinvents the Classic Baja Bug with Charm and Authenticity

The Twisted TBug is yet another rear-engined, air-cooled resto-mod - but it's different in all the right ways

The Twisted TBug is yet another rear-engined, air-cooled resto-mod - but it's different in all the right ways

Have you seen the Twisted TBug? Twisted, the friendly, Yorkshire-based modifier of classic Land Rover Defenders (and now owner of a marine division as well), has started offering a Volkswagen Beetle Baja Bug restomod too.

(If it starts doing Hillman Imps, our respective garages will look even more alike.)

Unsurprisingly, the TBug looks somewhat nicer than my Baja Bug, because Twisted are people who are used to doing things properly. The interior looks trimmed beautifully, the stance is just so (I’m tempted to have a word with the front end of mine and a grinder) and there’s a reinforced chassis, a new engine, new electrics and LED lights that don’t look daft.

The power output has been about doubled over the original, but it’s still making less than 80bhp, so it isn’t a fast car – but that doesn’t matter a bit. “What makes the TBug special is that it makes you smile every time you slide behind the wheel,” says Twisted founder Charles Fawcett.

“In a world of increasingly serious and complex vehicles, there’s something wonderfully refreshing about that.” As they might have said in the 1970s, I can dig that.

Unlike Twisted Defenders and Suzuki Jimnys, this car exists in the ‘special projects’ bit of the company’s offerings. Lots of personalisation and customisation is on offer and it’s the sort of thing you could get lost for days in with the designers – although Twisted has made three for sale already to its thinking, in grey, green and yellow. You can spend around £95,000.

Rather refreshingly, the TBug is a restomod that isn’t about adding silly power, keying a chassis down to the road or fitting an electric drivetrain to it. And better still, it’s one that’s based on a rear-engined, air-cooled, two-door German car but not a you-know-what.

Why Modern Car Safety Tech Is Driving Us Crazy and What Buyers Need to...

Cars are always on the lookout these days – and too many think drivers aren’t doing likewise

Cars are always on the lookout these days – and too many think drivers aren’t doing likewise

Recently we had a ‘situation’ on the road test desk. Nothing serious, just a logistical mess, but the eventual solution involved me blagging a lift up to MIRA from one of my What Car? colleagues.

George kindly bent his run from Brixton to the M1, passing through not just Finchley but also Archway, which is where I was waiting at the kerbside, crummy old road test backpack stuffed with the essentials: tape measure, gaffer tape, telemetry gear and very old, if-it-ain’t-broke laptop running VBox data-logging software.

The London-to-MIRA dash is one I do once or twice weekly. Three times if the proverbial hits the fan. Like a lot of this job, it’s a journey passed in solitude, so it was nice not only to be driven by somebody else but for it to be decent company, as George is.

He bought a Range Rover L322 in his early twenties so, in terms of raw tolerance for car-based financial turmoil, is up there with the best of us, only recently swapping the Rangie for a Mk5 Golf GTI (five doors, big teledial wheels, red: not my dream spec but still a lovely thing).

Playing passenger was enlightening. Free to observe, I could readily appreciate how much George was suffering at the hands of our car’s ADAS, which were running amok in London traffic.

No sooner had the lane keeping assistance made itself known than the road sign recognition would go off, then the driver attention monitor would extract its pound. I sat there thinking: this is what a dogfight sounds like when the entire squadron of enemy fighters achieve lock-on.

At this point I need to make it clear that George appeared to be doing nothing wrong. He seemed to be operating slickly in London traffic, which is, of course, as much art as science.

There’s give and take in the melee, but these systems don’t allow for that. They operate in a binary world where everything has a defined scope. At one point the driver monitoring went loco purely because poor George had had the temerity to glance out of the side window at an HGV speeding up to the dotted lines at a T-junction. Sensible to keep an eye on that sort of thing, no?

So it was interesting to be removed from the role of ADAS victim. A bit like the loved one who gets bullied by their boss but can’t quite see it and muddles through, only when you witness somebody else getting harried by these systems can you appreciate just how overwhelming it is. They go off constantly, chip, chip, chipping away.

I will say this, though: while they’re all subject to the same regulations and are all to an extent very annoying, these systems do work in subtly different ways, and that is starting to matter.

By MIRA, the two of us had reached the conclusion that we’re not far from ADAS behaviour being a part of the brand-loyalty equation. Performance, design, practicality and price are all big decision-influencing areas when it comes to car buying, but none of them are going to matter if the thing drives you up the wall every time you want to pop down to the shops.

Two things particularly matter: the manner of the intervention (everything from the timbre of the bong to the pick-up of steering auto action) and how simple the systems are to disable.

Some manufacturers do get it. They tend to be the ones that have traditionally put the driver first. BMW, for example, has a superbly gentle lane keeping action and lets you curtail the speed limit warning with one push on the wheel (seriously, who can stand bings going off at 52mph in a 50mph zone when, as every road tester can confirm, you’re really doing only 49.5mph?).

And with the launch of the Vantage Roadster, Aston Martin has introduced a physical ADAS shortcut button, right next to the exhaust and damping switches. To them, it’s that important.

On the other side of the equation there is Toyota. God I love Toyota, from Yaris to Land Cruiser, but its current, faintly paranoid ADAS are just infuriating. There’s even an alert to tell you when another car is wafting up behind you. Gratuitous or what? Would I like to take a break, as it suggests, 12 minutes into my trip? No, but I might like to steer off that cliff. The ‘off’ switches are also buried in fiddly menus and you can’t access them on the move. Not sure I’d buy one.

Or the Ford Mustang, whose conversion for Europe has been done with such cavalier ADAS coding that the display often erroneously pops off a ‘hands on the wheel’ bong on the motorway. I couldn’t live with the aggravation. Not for £75k.

It makes an extended physical test drive more crucial than ever, because it’s not just the driver these things annoy but the sorry passengers too.

How Next-Gen Range Extenders Could Spark an Electric Car Comeback

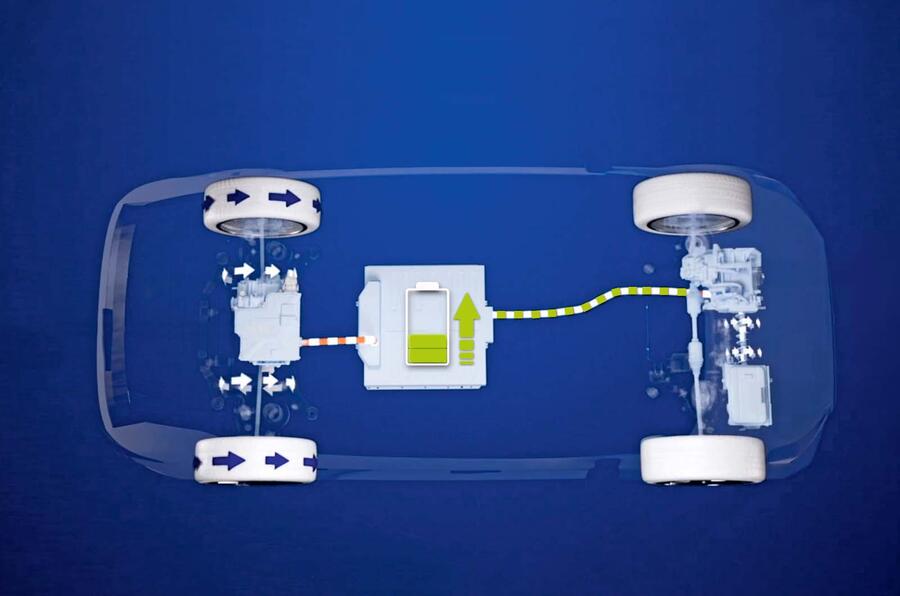

ZF’s eRE and eRE+ REx products, depicted above, are due to arrive in 2026.Ineos, Lotus and Volkswagen are all developing REx powertrains

Let’s wind back to 2012: Britain is gripped by Olympic fever as Vauxhall launches the Ampera and the UK’s first ‘plug-in’ hybrid decisively beats the Volkswagen Up to European Car of the Year glory in the process.

Within 12 months the Ampera will have a carbonfibre-cored rival in the unlikely shape of the BMW i3, another car using its petrol engine purely as a range-extender in what appears to be a movement gathering momentum.

Yet more than a decade later both cars feel like distant memories and range-extender (REx) technology – essentially where an engine charges a drive battery instead of powering the car itself – remains remarkably niche.

Mazda will sell you its MX-30 crossover with a dinky rotary generator on board, while LEVC London cabs deploy REx tech on a larger scale. But most customers opt for a battery-electric vehicle (BEV) or parallel hybrid and ignore a once-pioneering stepping stone between the two camps.

ZF reckons that is about to change. The German automotive and industrial tech giant has its hand in all manner of components and its 8HP eight-speed automatic transmission is a mainstay of the industry, with dozens of applications since its late-noughties introduction.

ZF’s latest range-extender systems, eRE and eRE+, are designed to speed up car makers’ evolution of hybrid and EV technology – and help them mould around increasingly tumultuous market conditions.

“It could potentially revitalise the somewhat sluggish electric vehicle market in Europe and the US,” says the company. “Major manufacturers like Hyundai, Ford and Stellantis are showing interest in range-extender technology and planning to launch vehicles equipped with it within the next two years.” Its halo gearbox certainly has a good track record of breaking down rivalries and supplying multiple, competing manufacturers all at once.

So what’s new compared with a decade ago? “When you look at the history of range-extenders, [engines] like those in the i3 were designed to help you in utmost urgency,” says ZF’s e-mobility R&D boss Otmar Scharrer. "This has changed. Range-extenders are now much stronger and more powerful.”

Cooling, packaging and refinement have improved as REx cars move away from shrunken engines to proven larger units with a strong, efficient mid-range and capable of running frequently rather than being dipped into sparingly. A naturally aspirated petrol four-pot is optimal.

While neither of ZF’s new offerings drives the wheels directly – it’s key to their MO – they can work with up to 200bhp of engine output and either plug and play with a manufacturer’s existing engine and motor or use a clutch and differential to create a more flexible set-up where an intermediary generator can drive the wheels. Both options can hook up to 400V or 800V charging architecture.

Scharrer sees huge market potential in areas where charging infrastructure remains a barrier to EV sales success. “I hear comments that this is a very short-term technology and that regulations aren’t following,” he laments. “But if you have a car capable of going 155 miles fully electric, then it has a range-extender for the countryside, why should you be banned from driving it in the city?

“We involve ourselves as much as we can in regulatory discussions. In China, to keep the status of a ‘new-energy vehicle’ [EVs and plug-in hybrids], you must not connect the internal combustion engine to the wheels.

The EU has not finally decided what to do with range-extenders, but I think they realise that this is an interesting opportunity to offer a product which is less dependent on rare materials and cell chemistry because you need a significantly smaller battery.

“They want to understand what the pros and cons are. The whole mobility community is ready for these discussions, because we need them. The past regulation of BEVs has shown that we cannot push things into the market against the customers’ will.

The easier a solution is, the higher its chance of surviving a long time. And this is quite an easy solution. I personally expect that we will see it beyond the next five to 10 years. I think there will be plenty of applications which really excite people.”

Confident words when sales of new hybrids are due to cease in Europe after 2035. Indeed, Ineos, Lotus and Volkswagen are three more names reportedly dabbling with REx powertrains as we speak. Maybe the Ampera was right all along.

Jaguar C X75 The Greatest Hypercar That Never Made It to Production

Sometimes a brief drive of a test mule is the only taste you'll ever get of a new machine

Sometimes a brief drive of a test mule is the only taste you'll ever get of a new machine

The difference between a concept car and a prototype is huge. It’s the difference between a piece of motor show eye candy and a viable proposition that has been made convincing enough to actually prove said concept.

This is the continuation of a thread I started recently, explaining the peculiarities, pressures and, often, disappointments that are associated with test drives in concept cars.

When you drive a concept car, you feel like a significant chunk of the story you write is about the art of the imagined. If this thing comes to be, just what might it be like? Such a car could supply perhaps 30-40% of that picture – or just 4%. But a prototype might get 90% of the way there.

There’s a greater sense of occasion to driving a prototype; manufacturers usually only allow it when they’re building up to introducing something really important. At this stage, a whole lot more has already been invested and more still is on the line. You might be driving one of only two or three very valuable examples of something currently in existence.

Sometimes, the full significance of what you’re doing isn’t apparent at the time. Back in the autumn of 2006, I went to Hethel, Norfolk, to ride in, rather than drive, a prototype of something called a Tesla.

The Roadster was, of course, a stretched Lotus Elise with so many laptop batteries where the four-cylinder engine would otherwise have been. I remember still how uncannily responsive and linear the performance felt – and that was while the car still had a two-speed automatic gearbox, so it tended to shift at about 60mph in a way that was noticeable enough to, well, lunch gearboxes, it would later turn out.

Did it feel like the start of something that would change the car industry? Not entirely. But it was clearly a more credible product than anyone with whom I spoke about it at the time was ready to believe. I wouldn’t have known that much from a show car.

There are prototype drives, by contrast, when you know precisely what strategic significance you’re dealing with. Little can give you a better idea of that than turning up at the gates of a brand-new factory built to manufacture the car you’re about to sample, a model that is being hailed as the saviour of its long-ailing creator.

That’s how I first sampled an Aston Martin DBX: with a car load of engineers along for the ride through the Welsh mountains. (“What do you think, Matt?” No pressure, there, then…)

And, just occasionally, you know that a test drive in a prototype is all you’re ever going to get. That is exactly how it was with Jaguar’s great aborted hybrid hypercar, the C-X75, when we managed a handful of laps of JLR’s Gaydon high-speed and handling circuits in 2013.

This was the time of the hypercar ‘holy trinity’. Jaguar had been bold enough to invest big and, with the help of Williams Advanced Engineering, take its particular vision for such a car all the way through to a highly polished place.

But, rather crushingly, it had also already decided not to build it. That competitors from Porsche, Ferrari and McLaren were all coming to market at the same time was too great a risk. Above all, JLR couldn’t afford another XJ220.

The car certainly didn’t deserve description in those terms. I never drove a LaFerrari, but I have driven both a McLaren P1 and a Porsche 918 Spyder, and honestly, the C-X75 was right up there.

It had bucketloads of star quality; its chassis and steering were outstanding; and its 1.6-litre, 10,000rpm twin-charged four-cylinder combustion engine topped the lot. It was like some mutant superbike motor backed by epic electric torque fill. It was monumental.

The C-X75 might well be the greatest performance car that the British industry never made. And being in the position to learn that – however bittersweet it may feel on reflection – is why you don’t turn down drives in prototypes.

Why the Nissan Micra’s Reliable Reputation Is Its Secret Strength

Early Micras majored on the mundane but were none the worse for it

Early Micras majored on the mundane but were none the worse for it

Is there a supermini whose character, over the years, has changed as much as that of the Nissan Micra At least in the eyes of its maker, if not in the minds of its buyers.

The first-generation Micra was a sturdy, box-like thing, as plain as cars come. The second one was much more rounded and funky, Europeanised, even, to the point that it won Car of the Year in 1993 – the first Japanese car to do so.

The third model took the idea ran with it, going more upmarket still, being cutesy and classic, with Bakelite-style interior switchgear and traditional fabrics. It felt expensive, and maybe, to make, it was.

And then came the 2010 disaster: it was a car that felt so cheap and rough that when we said as much, the good people of Nissan agreed. Sometimes, they explained, they would take offence at a verdict and tell us why we were wrong, or why they thought we were wrong, but in other cases a drubbing in the media would give them a way to convince their bosses they should do it differently.

This was one of those cases, and Nissan duly did better with a 2016 Micra that was a markedly decent thing, if not markedly interesting. It went off sale in 2022.

In the meantime, Nissan’s rivals had been making superminis that were sometimes great and sometimes fine but fundamentally consistent; at least they were always trying to be the same thing.

Ford made a bunch of Fiestas that each felt every inch like Fiestas. Even now Renault’s new Clio is trying to occupy basically the same position as the Nicole-Papa original, as the most chic of the superminis.

All kinds of cars try to retain their core ethos, in fact. If you climbed into, say, a BMW 3 Series today, I think you could probably tell it’s trying to do basically the same thing as a 3 Series from three or more decades ago.

But here comes another new Micra. Yes, it’s another reinvention, this time as a cute electric car, but, it seems, it’s different from previous Micras not only in powertrain but also in character (again). “Think you know me? Think again,” said the teaser on Nissan’s website ahead of the launch. “It’s been a while, and I’ve had a glow up. Let’s meet up soon. You won’t believe the difference.”

Won’t I? I wonder if that’s (a) true and (b) a shame if (a) is the case. Because while Nissan may well think its Micra has done different things, then, 2010 calamity aside, I wonder how much buyers have noticed or cared.

Like it or not, and I get the impression Nissan doesn’t like all of it, the Micra has gained a reputation as steady and reliable if uninteresting transport. As its exterior designer Yongwook Cho told us, the new car’s design is meant to make it “a grandma car no more”.

That’s a theme you come across now and again in consumerism: a producer of something – cars, clothes, radio shows – seeks to throw off an image as being popular with the elderly and tries to bring in a new, more youthful audience.

And to an extent I understand it, if the current image is actually harmful. I know people deep into their sixties who still think Jaguars are cars for old men, and they wouldn’t buy one even if they could.

So I get why Jaguar, as a maker of glamorous sports cars, which it would be nice to think it will be again soon, would try to make itself attractive to a younger audience. Because even if the young haven’t got any money, it will appeal to the old who don’t want to seem old.

But is being a supermini admired for its sturdiness, reliability and sensibleness really so bad? As people stay both in work and healthy for longer, the difference between young and old is less marked than it was.

And whatever the age, what’s so bad about a supermini that’s reliable, easy to use and not sold by spivs? In short, I think it’s possible to make a supermini that will appeal to everyone, without cheesing off a certain section of drivers by implying it’s not for them. Assuming they’re listening, of course.

Buyers have decided for themselves what the Micra is in the past. There’s no reason to think they won’t this time, too.

UK’s New Electric Car Grant Sparks Debate Over Fairness and Future of EV Adoption

One senior industry official described the scheme as one that would “divide opinion”

One senior industry official described the scheme as one that would “divide opinion”

An overwhelming majority of car makers have craved the return of incentives to boost demand for electric cars in the UK, with ever-greater desperation since the start of 2024.

The ZEV mandate introduced by the government 18 months ago meant manufacturers faced significant fines for not selling enough EVs, and barely an interview with a top UK executive from a legacy car maker has gone by - several in this column - without them saying they need government help to hit those targets because there is not enough true market demand for EVs.

To date, car makers have managed to comply with the mandate and avoid fines. Yet with their own discounts on new EVs totalling £6.5 billion in an effort to tempt buyers into them, according to Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders data, it has come at a huge cost.

Against £6.5bn of discounts, the £650 million put aside by the government for the Electric Car Grant (ECG) looks like loose change. No wonder one senior industry official described the scheme to me as one that would “divide opinion”, and not only for the sums involved.

The ECG is banded with discounts of £3750 or £1500, depending on complex criteria around the intensity levels of carbon in the grid of the country of manufacture of each EV.

We await details of how this will work, but one interpretation of it is as a back-door way of excluding low-cost Chinese-made EVs from the scheme. Rather than apply import tariffs like the EU has done on such cars, the UK looks to have chosen not to subsidise them and instead has created a ‘Science Based Target’ as a political smokescreen to hide behind.

That the ECG doesn’t appear to factor in carbon emissions from the shipping of cars would surely have those in China wondering why they’re being hit while cars coming from nearby Korea and Japan aren’t.

If all the discounts were only the lower £1500 figure, the ECG would cover subsidies towards just over 430,000 new EVs. Some 225,000 EVs were sold in the UK in the first half of this year, and given that the ZEV mandate’s target is ramping up each year, the ECG money could conceivably run out by late spring next year.

No wonder many of those who have welcomed the grant for now have used the opportunity to call for further investment and support to help build a better infrastructure to serve the growing number of EVs on the road.

More fun and games are to come, then, but in the short term the ECG will at least have the desired effect by providing a boost to EV sales in the UK. The government will call it a success as a result; car makers will get a helping hand towards ZEV mandate compliance.

“There is no single country in the world where EVs don’t depend on incentives,” Jato senior analyst Felipe Munoz told me, referring to latent concerns around the likes of price, range and infrastructure. That’s true even in the EV utopia of Norway, and it's true in China, where EV/PHEV buyers are “getting their licence plate faster and at lower rates”.

He added: “The truth is that without the active role of the governments, EVs can’t go on by themselves."

Why Affordable Hot Hatchbacks Are Disappearing and Why It Matters for Car Lovers

The hot hatches still on sale today cost from £40k – but most are being taken off sale

The hot hatches still on sale today cost from £40k – but most are being taken off sale

It’s taking a while, like closing an ill-fitting lid on a plastic kitchen container. But another corner on the ‘affordable hot hatch’ tub is clicking shut, and, unlike sometimes previously, I don’t think a corner on the other side is about to pop back open again in defiance.

Which is a slightly clumsy way of avoiding the ‘nail in the coffin’ cliché. Also I think it’s vanishingly rare (I could be wrong) that a coffin lid’s opposite corner creeps open again when someone is hammering down the opposite side.

Anyway, what I’m saying is that Ford is preparing to unalive the Focus ST. Production ends in November, and it has been removed from price lists in the UK because all the remaining ones are accounted for.

And this time I don’t think anyone is about to launch a new affordable petrol hot hatchback you could choose to consider instead. Although do go ahead and prove me wrong, somebody, please.

It seems like a very long time, partly because it is, since my mate Jason, when he was a young man, bought a Citroën Saxo VTR on low- or no-interest finance and got free insurance thrown in. It even feels like a long time, although it isn’t, since Hyundai offered the i20 N for under £25k.

The hot hatches that remain on sale today – and there are fewer than a handful, including the Focus ST – are basically £40k cars. So it has sort of been true for a while, but only now, with the demise of the Focus ST confirmed, does the malaise feel as terminal as it clearly has been for quite some years now. The hot hatch era is gone.

Should one be sad about it? I think so. Because not very long ago, if you were young and you wanted to get into cars, you bought an ordinary hatchback with a bigger engine and some tidy suspension, and you had a nice time driving it. Then, when you were older and had a house and some money, you bought a sports car. But the mood was established early on.

What’s the option now? New hot hatchbacks are too expensive, and while some fun electric cars, like the Alpine A290, are becoming affordable, that will be little solace to you if you live in a rented flat, because buying an Alpine will be too expensive, and your rented accommodation has no charger anyway.

A used one? This is a possibility, if it hasn’t already been stolen or crashed. Or how about an affordable used sports car? This is also a nice idea, but it requires one to choose wisely. Since April, cars registered between 2001 and 2017 have had some wacky VED rates applied.

My Audi A2 emits 119g/km of CO2 and costs £35 a year to tax. I like the lovely idea of a bargain Porsche Boxster, which emits 239g/km of CO2 – twice the amount, so naturally that will cost twice as much as the Audi to tax, yes? Actually no. It is £735 a year, 21 times as much.

I doubt that banning new affordable fun cars and making thousands of old ones exhaustively expensive to run was the aim. We live in a time of complex regulation and unintended, unexpected consequences. But if you were feeling ostracised by ‘the system’ or ‘the man’ (or ‘the woman’) and were having uncharitable thoughts when a VED bill of £760 arrived (for 255g/km-plus), I completely understand why.

There are fudges, loopholes, gaps in the system, of course. It’s why Ford’s main performance car in the UK is now a Ranger Raptor and there was a story in a newspaper the other day complaining about the number and size of American V8 pick-ups being privately imported to Britain.

Well, if you make a satisfying domestically approved V8 near impossible to come by, that’s what people will do.

And I believe in the car enough, both as the most brilliant and convenient form of transport and as a fun object for enthusiasts and hobbyists, that at whatever your budget, I can see a way into having and enjoying one.

But as the affordable performance Ford disappears from price lists for the first time in my half-century life, it has never felt quite so difficult as today.