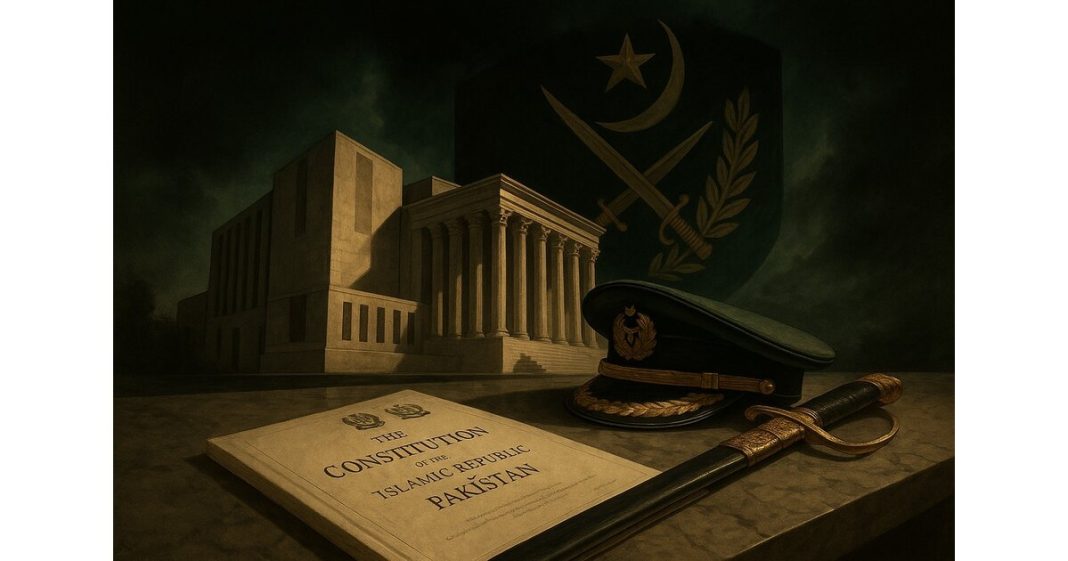

A specter of profound and perilous change haunts Pakistan’s military and political landscape, embodied in the Constitution 27th Amendment (Twenty-Seventh Amendment) Act, 2025, which has already passed the National Assembly and Senate with a two-thirds majority. This is no mere administrative reshuffle or simple legislative update; it is a meticulous and audacious re-engineering of the Pakistani state itself, a constitutional coup executed not with tanks and generals in the streets, but with legislative text and parliamentary votes.

The amendment executes a two-pronged assault on the nation’s democratic architecture, simultaneously subjugating the judiciary and coronating the military. It seeks to dismantle the traditional checks and balances that form the bedrock of any democratic society, creating a new constitutional order where judicial independence is systematically curtailed and military authority is not just paramount, but permanently and unassailably entrenched.

This move, as analyzed from both a military-strategic and a constitutional-legal perspective, signals a deliberate turn away from the principles of civilian supremacy and the separation of powers, charting a perilous course towards a formalized, constitutional praetorianism that threatens to transform Pakistan from a struggling democracy into a militarized state with a democratic facade.

The Judicial Coup: Dethroning the Supreme Court

The first pillar of this new architecture is the systemic dismantling of the judiciary as an independent check on state power. The amendment’s most audacious move is the creation of a new Federal Constitutional Court (FCC), a body that effectively usurps the Supreme Court’s historical role as the final arbiter of constitutional questions and fundamental rights.

Through the rewriting of Article 175 and related provisions, the Supreme Court is to be “dethroned” and relegated to the status of a mere appellate court for civil and criminal matters, a body some legal experts have derisively termed a “Supreme District Court.” The new FCC’s decisions will be binding on all other judicial bodies, including the Supreme Court itself, creating what amounts to a judicial hierarchy where the Supreme Court, once the apex of Pakistan’s legal system, is now subordinate to a newly created body.

This represents a radical restructuring that senior former judges and leading lawyers have warned would “permanently denude” the Supreme Court of its constitutional jurisdiction, something they say no civilian or military regime has previously attempted in Pakistan’s history.

The implications of this shift are profound and far-reaching. Historically, the Supreme Court of Pakistan has been the final arbiter on constitutional questions, federal-provincial disputes, and fundamental-rights petitions under Article 184(3). It has been the forum where the opposition, civil society, and ordinary citizens could challenge constitutional amendments, emergency powers, and authoritarian measures. By shifting this power to a new Federal Constitutional Court whose design is more heavily shaped by the executive and parliamentary majority, the amendment weakens the classic separation of powers and creates a parallel and superior court that is more susceptible to political influence.

The 27th Constitutional Amendment after incorporating changes recommended by the Standing Committee.

— Benazir Shah (@Benazir_Shah) November 11, 2025

The FCC will exclusively hear federal-provincial and inter-provincial disputes and key constitutional questions, and critics fear that in the hands of a central government closely aligned with the military establishment, the FCC could tilt systematically in favor of the federation, eroding the spirit of the 18th Amendment’s devolution of powers to provinces. Over time, provincial autonomy could be hollowed out judicially rather than by openly amending the devolution clauses, representing a centralization of power in Islamabad that undermines the federal character of the Pakistani state.

To further cement executive control over the judiciary, the amendment introduces subtle but powerful mechanisms for influence that go beyond the mere creation of a new court. The amendment empowers the president, on recommendation of the Judicial Commission of Pakistan, to transfer High Court judges, with a judge refusing transfer deemed to have retired. This creates a chilling effect on judicial independence, as any “troublesome” judge who makes decisions unfavorable to the government or military can be moved, with refusal meaning forced retirement.

Read more: Trump-Netanyahu Peace Proposal is a Trap? Doomed to Fail?

The allure of power is made even more tangible by granting FCC judges a higher retirement age of 68 compared to 65 for Supreme Court judges, and by placing the Chief Justice of the FCC above the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the order of precedence. This creates a new judicial hierarchy where ambitious judges may prefer aligning with the FCC and its appointing authorities, weakening the culture of independence across the superior judiciary.

The 27th amendment has been passed behind closed doors without the consent of the people. The Pakistani constitution is unrecognizable and no longer respected as a unifying, democratic document that preserves individual freedoms, provincial autonomy and democratic integrity.

— Zulfikar Ali Bhutto ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو (@BhuttoZulfikar) November 10, 2025

The result is a fragmented apex authority where citizens and politicians lose the clarity of “one final court” for constitutional questions, and where the Supreme Court’s relatively robust tradition of taking suo motu human-rights cases is replaced by a new body whose independence is untested and whose composition can be more easily shaped by the ruling coalition.

The Military Coronation: Creating an Unchallengeable Commander

Concurrent with this judicial overhaul is the constitutional coronation of the Army Chief, a move that transforms the military from a powerful institution operating largely outside formal constitutional constraints into one that is explicitly and permanently embedded at the apex of the state structure. The amendment rewrites Article 243 to create a new, all-powerful post of Chief of Defense Forces (CDF), a role that is to be concurrently held by the Army Chief. This move abolishes the position of Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, a four-star post currently held by General Mirza and set to be dissolved when he relinquishes office on November 27th.

The dissolution of this office also renders the Joint Staff Headquarters obsolete, leaving two of its most critical organizations dangerously headless: the Strategic Plans Division, which is responsible for Pakistan’s nuclear weapons, and the three strategic commands that have strategic assets supporting those weapons.

This void is to be filled by the Army Chief, who would then become the primary military representative in the National Command Authority, the country’s highest decision-making body on matters of defense and security. This would not only sideline the Prime Minister but also give the Army Chief an almost unchecked and decisive say in matters of war and peace, including the catastrophic decision to use nuclear weapons.

Fear of one man has forced the regime to :

1. Take back party symbol

2. Rig elections 2024

3. Installing PMLN which won only 17 seats in power

4. Pass 26th amendment

5. Pass PECA laws

6. And now 27th amendmentAll for fear of one man Imran Khan who has been in jail…

— Mohammad Zubair (@Real_MZubair) November 10, 2025

The hyper-concentration of military authority is further solidified by granting officers promoted to five-star ranks, Field Marshal, Marshal of the Air Force, Admiral of the Fleet, a lifelong rank, uniform, and privileges. More significantly, these officers are made removable only through a procedure similar to presidential impeachment under Article 47 and are extended immunities akin to those of the President under Article 248.

This transforms the top military leader from a time-bound public servant subject to ordinary turnover and scrutiny into a constitutionally entrenched, semi-political figure who outlasts any civilian government. The implications are staggering; this greatly raises the cost of accountability for alleged abuses of power, corruption, or unconstitutional actions by the top brass, and symbolically reinforces the idea of the army chief as a permanent guardian of the state rather than a professional military officer serving at the pleasure of elected civilian leaders.

To complete this consolidation of power, the amendment proposes the creation of a new National Strategic Command, a body that would absorb the now-headless Strategic Plans Division and strategic commands. It would be led by a commander, likely a three-star officer rather than the four-star Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff, appointed by the Prime Minister on the recommendation of the Army Chief.

This is a crucial detail that reveals the true intent of this legislation: it is a clear and deliberate effort to bring Pakistan’s nuclear weapons and strategic assets under the direct and total control of the Army Chief. Historically, the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff position, created in 1976, was originally intended to rotate among the services, Army, Air Force, Navy, though the Pakistan Army discontinued this rotation, and the Chairman has since always been from the Army.

However, the Chairman was appointed by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister, meaning the Army Chief did not have direct say in this appointment. For the Pakistan Army, nuclear weapons were not about war fighting; they kept nuclear weapons under a four-star Army officer to provide some separation from direct Army Chief control. This shift is partly motivated by a desire to elevate Pakistan’s geopolitical profile, a line of thinking influenced by former U.S. President Trump’s repeated claims of having “stopped a nuclear war” between India and Pakistan.

Trump’s statements have spurred the current Army Chief, General Asim Munir, to view direct control over the nuclear arsenal as a tool of international prestige, transforming nuclear weapons from a deterrent into a symbol of Pakistan’s rising geopolitical status.

The Military-Strategic Contradiction: Ignoring Operational Lessons

The strategic and military implications of this power grab are as alarming as the constitutional ones, representing a fundamental misreading of modern warfare and a dangerous regression to outdated models of military organization. The move toward a single, supreme military commander blatantly disregards the hard-won lessons from recent military engagements, particularly the four-day operation in May known as Operation Sindoor in India and Operation Bunyan-un-Marsoos in Pakistan. That conflict, which is currently on pause, highlighted the critical importance of joint-service cooperation and the technological prowess of the Pakistan Air Force.

The international community’s assessment of the operation was that the Pakistan military, on the strength of its Air Force’s performance in air-to-air operations on the first night, should be supported as a peer competitor to the Indian military. The briefing to the international media on May 8th was led not by the Director General of ISPR, a three-star Army officer, but by Air Vice Marshal Aurangzeb, a two-star Air Force officer.

This was a clear acknowledgement of the Air Force’s technical expertise and its central role in modern warfare, as he was the best person to explain what the Pakistan Air Force accomplished, to present Pakistan’s new concept of multi-domain operations at the operational level of war, and to answer questions from the international community with replies that satisfied them.

The core competencies of the services are fundamentally different, and this difference is rooted in their force structures. The Army’s force levels are structured around manpower; it is about people, more about numbers, and less about technology. In contrast, the Air Force and Navy have force levels structured around platforms and technologies.

As more and more technologies come into warfare, these are the services that understand and adopt technology faster than the Army. This is why, for instance, when Pakistan established the Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Computing, a technology-intensive organization, it was placed under the Pakistan Air Force, not the Army.

Read more: The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Hinge: When Pakistan’s Story Turned

The amendment’s logic flies in the face of this reality, subordinating the Air Force and Navy to an Army Chief who, due to the Army’s practice of “deep selection” rather than strict seniority, could be junior in service to the Air Force Chief and may understand much less about technology. Yet constitutionally, this Army Chief would have the last word on deterrence and conventional war, an arrangement that does not help Pakistan’s military deterrence capabilities.

The amendment also completely ignores the growing strategic importance of the Pakistan Navy, which is set to expand its capabilities significantly in the coming years. By 2028, the Pakistan Navy will receive eight Hangorl-class submarines from China, equipped with Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) technology, significantly boosting its underwater capabilities. The Navy’s role is expanding beyond traditional boundaries, and it is poised to play a crucial role in the stabilization of the Western Indian Ocean region, in conjunction with the PLA Navy’s presence in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa.

This expansion requires a high degree of technological expertise and strategic autonomy, both of which would be undermined by subordinating the Navy to a single, army-centric commander. The current structure, where all three services have an equal say and conduct coordinated operations, has proven to be a more effective model for maintaining credible deterrence. By contrast, the proposed changes would not only undermine this deterrence but also increase the risk of a hot war between India and Pakistan, a conflict that would have devastating consequences for the region and the world.

The amendment’s approach stands in stark contrast to the lessons offered by the military reforms of China’s People’s Liberation Army, which represents the cutting edge of operational warfare today. In 2014, the PLA issued its military strategy, and in 2015, it conducted structural reforms that drastically cut the land forces and redirected money and technology to the Rocket Force, the PLAF (Air Force), and the Navy.

As technology evolves and the operational level of war advances, cutting-edge military forces prioritize technology-intensive services over manpower-heavy land forces. Yet the 27th Amendment represents a regressive step, a move back to a time when manpower was valued over technological superiority. The irony is staggering in the quest to grant one man supreme power, the very foundations of Pakistan’s credible military deterrence, joint-service synergy, technological agility, and distributed expertise—are being systematically dismantled.

The Democratic Threat: Militarization of Law and Politics

The amendment does not, as far as the publicly reported text shows, explicitly expand military courts’ jurisdiction over civilians. Its impact comes from context and architecture. Since May 9, 2023, protests following Imran Khan’s arrest began, and Pakistan has increasingly used military courts to try civilians accused of attacking military installations. International actors, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, have condemned these trials as lacking transparency and due process.

With this background, challenges to military trials and to laws expanding military jurisdiction over civilians rely heavily on constitutional litigation. If those challenges now go to a Federal Constitutional Court whose creation, membership, and incentives are intertwined with the same political-military complex, there is a serious risk of rubber-stamping rather than robust review. The weakening of the Supreme Court and the creation of a more executive-friendly FCC pose a grave threat to fundamental human rights, making it harder for opposition parties, activists, and ordinary citizens to get relief against enforced disappearances, censorship, or politically motivated military trials.

The persistent state of tension between India and Pakistan creates a volatile environment where a single, unchecked decision-maker could easily trigger a catastrophe. The concentration of power in a single individual who can override the National Command Authority and take decisions about war and peace with minimal checks and balances is an extremely dangerous proposition. The proposed changes would not only fail to help Pakistan’s deterrence but would also bring India and Pakistan closer to a hot war, which would not help the region, would not help the development of the two countries and the region, and would have serious global consequences.

Combine the key elements of the 27th Amendment: a weaker, sidelined Supreme Court with reduced constitutional role; a new FCC that may be more executive-friendly and less historically rooted in protecting dissent and opposition rights; and an Army Chief who is now also the CDF, with lifelong rank, immunity, and nuclear influence. Critics argue this triad will make it harder for opposition parties, activists, or ordinary citizens to resist the militarization of law and politics, will raise the political cost for any future civilian government that might wish to reassert control over the military, and will normalize a model where the military is not just powerful in practice but written into the constitutional apex. This is a classic marker of a praetorian system rather than full civilian democracy, a shift from “civilian supremacy” to what might be termed “constitutionalized praetorianism.”

The Crossroads: A Choice That Defines a Generation

Ultimately, the 27th Amendment is more than a piece of legislation; it is a declaration of intent. It signals a deliberate turn away from the collaborative, technology-driven future of modern warfare and a regression towards a model of centralized, autocratic control that has been proven obsolete by the very military operations Pakistan has recently conducted.

The core adverse risks are clear: democratic erosion through the hollowing out of the most powerful institutional check on both government and military; judicial subordination through transfers, altered hierarchies, and incentives that favor alignment with the executive-military establishment; hyper-concentration of military authority in a single individual with lifelong rank and immunity; and civilian vulnerability in a context of expanding military trials and crackdowns on dissent.

The nine corps commanders of the Pakistan Army, who are the true source of the Army Chief’s power, therefore stand at a historic crossroads. Theirs is not merely a decision about a piece of legislation, but a choice that will define the character of the Pakistan military and the future of the nation for a generation. They must decide whether to endorse a structure that prioritizes the ambition of an individual over the collective strength of the armed forces, and whether to lead their nation down a path of heightened risk and instability, or to uphold the principles of modern military strategy and safeguard the future of their country.

The bill is contrary to the verdict of the four-day operation, which demonstrated the critical importance of Air Force technological superiority and joint operations. The corps commanders have the authority and understanding to evaluate military implications, and they have a responsibility to ensure decisions serve Pakistan’s best interests. They must choose between loyalty to the ambition of a single individual and the long-term security and stability of their nation. The stakes could not be higher, and the world holds its breath, hoping that wisdom will prevail over the intoxicating lure of absolute power.

The author is a Seattle-based entrepreneur, technologist, and social activist. He can be reached at LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/asad-faizi/ or email:asadfaizi@gmail.com

The opinions presented here reflect the author’s personal analysis and experience, which may not fully align with the publication’s editorial outlook.