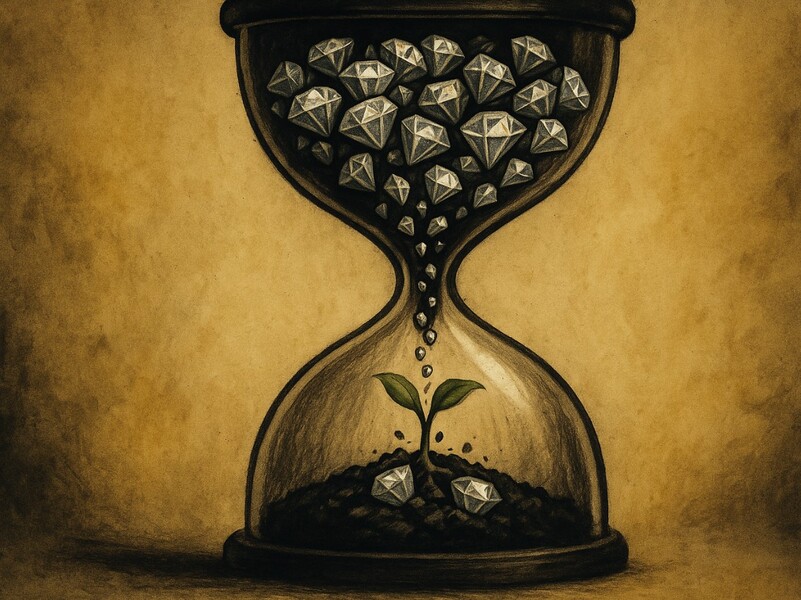

We live in societies where value is something we assign, not something inherent. If something generates profit, we call it valuable. If it does not, we strip it down for parts and treat it as expendable. This inversion leads us to dismiss the essential and abundant as worthless, while elevating the inherently useless to the status of priceless treasure — so long as someone profits.

Few examples are clearer than how we treat the planet itself. The environment that sustains humanity is overlooked precisely because it surrounds us. Forests become nothing more than timber reserves or land for expansion. The Amazon shows this clearly: in the 2010s and 2020s, deforestation surged to clear space for cattle ranching and soy, even though the forest is one of the world’s most vital carbon sinks. Air, water, and soil are expected to provide endlessly, but are not considered assets until they can be monetized.

Diamonds, by contrast, are revered as symbols of wealth and permanence. Not because they are rare in any real sense — some planets see diamonds rain — but because companies taught us to believe they were valuable. De Beers’ 1947 advertising slogan, “A Diamond is Forever,” manufactured the cultural value that still defines diamonds today. And so we degrade forests, rivers, and ecosystems for the sake of a shiny stone with no intrinsic worth, while ignoring the one thing in the universe truly irreplaceable: a planet that can support human life. This is the only planet with trees. The only place with oxygen levels suitable for complex life. There is only one Earth.

The Comfort of Complacency

In pursuit of all this comfort, we have lulled ourselves into complacency. At first, by insisting there was plenty of time and that profitable solutions would arrive if we only waited — because heaven forbid we dent the GDP. And now? By adopting a fatalistic attitude: claiming that it is already too late, that bold policies would cost too much. Few ask the obvious question: where will these economies exist if the planet that sustains them were to collapse?

If we have locked ourselves into a system that is unsustainable by design, it should go without saying that we must change the system. We cannot ignore the disconnect of relying on systems looking for infinite growth, in a physical reality where we have limited resources.

Delay and Denial: A Century of Excuses

Manufactured Doubt

Our history with climate action is a history of delay. When public transport could have broken dependence on oil, governments clung to the automobile industry because it was profitable. Electric cars were first imagined more than a century ago, yet they languished until they could promise shareholder returns. The same pattern repeats in food. Instead of cutting waste or moderating meat consumption, we wait for lab-grown meat to become indistinguishable from the real thing — a solution that can be marketed and monetised.

But this culture of postponement is not accidental, it’s been actively manufactured from the start. In the 1970s, Exxon’s own scientists warned that burning fossil fuels would warm the planet by 1–2 °C by mid-century, predictions that proved eerily accurate. Instead of acting, Exxon launched a campaign to cast doubt on climate science.

Organised Resistance

In the late 1980s, as NASA’s James Hansen testified to Congress that global warming was already underway, the oil and auto industries created the Global Climate Coalition to lobby against international agreements. In the 1990s, coal companies poured money into think tanks like the Competitive Enterprise Institute, funding advertisements that declared “CO₂ is life.” When outright denial lost credibility in the 2000s, the strategy shifted to delay: promoting “clean coal,” carbon offsets, and distant technologies like carbon capture as reasons to avoid systemic change. Today, the same corporations run glossy campaigns about net-zero futures while still spending billions on new oil and gas exploration.

At every stage, the purpose has been the same: to stall. The result is that emissions have accumulated past safe limits, ecosystems have been cut down or poisoned, and the initial window for easy solutions has closed. What remains are harder choices, choices that demand sacrifice — and decades of denial have left us unprepared to face them.

The Science of What’s Still Possible

Planetary Boundaries

But we have not yet reached the point of no return. Recent studies show that while the damage is severe, the future is not locked. And researchers have mapped what it would take to bring humanity back within “planetary boundaries,” the set of Earth system processes that define a safe operating space for civilization.

Each boundary has three zones. Below the line is the safe space where Earth’s systems remain stable. Crossing into the zone of uncertainty increases the risk of disruption, even if impacts are hard to predict. Beyond lies the high-risk zone, where irreversible damage occurs.

In the original Stockholm Resilience Centre assessments (2009 and 2015), four boundaries were judged to be breached: climate change, biodiversity loss, deforestation, and nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. But an updated analysis published in Nature in 2025, using a more detailed global model, paints an even starker picture. It shows that five boundaries were already outside the safe zone by 1970, and six of nine are breached today. With biodiversity and nutrient flows especially deep in dangerous territory.

Scenarios for the Future

The same study, led by Detlef van Vuuren, projected future outcomes, using three “Shared Socioeconomic Pathways” or SSPs:

- SSP2, the “middle of the road” pathway: assumes governments continue with current policies. This is essentially business as usual. Under this scenario, by 2050 most boundaries worsen. Climate change deepens, nutrient pollution stays high, and biodiversity keeps falling.

- SSP3, a more pessimistic pathway: assumes weak global cooperation, slower technology development, and higher population growth. Here, almost all boundaries are pushed further into dangerous territory by mid-century.

- SSP1, a more optimistic pathway: assumes more cooperation, better technology, and slower population growth. Conditions improve somewhat compared to the other scenarios, but most boundaries remain breached. Incremental improvements are not enough to return us to safety.

A Sustainability Package

The same study tested a more ambitious “sustainability package.” This combined climate policies aligned with the Paris Agreement with reforms in food and resource systems: shifting diets toward the EAT–Lancet planetary health diet (with more plant-based food and less red meat), halving food waste, using water more efficiently through recycling and modern irrigation, and applying fertilizers more precisely to avoid nitrogen and phosphorus runoff. With these changes, some boundaries could be pushed back toward their 2015 levels by 2050. Air pollution falls, nutrient flows improve, and pressure on land use eases. Climate change remains above the safe threshold but begins to decline, and biodiversity loss slows, though recovery takes longer.

A second Nature study from 2024 looked at who contributes most to these problems. Using consumption data from 168 countries, it found that the richest 10 percent of people are responsible for up to two-thirds of the overshoot, and the top 20 percent for as much as 91 percent. The poorest half of the world contributes almost nothing. This matches other reports, such as an Oxfam study in 2023 showing that the richest 1 percent produce more emissions than the poorest two-thirds of humanity combined. The 2024 study also found that if the top 20 percent simply adopted the lowest-impact consumption patterns already common within their own group — eating less meat, wasting less food, flying less often — global environmental pressures could fall by a quarter to a half. Reforms in food and services alone would be enough to bring land use and biodiversity back within safer limits.

The conclusion from these studies is straightforward. Returning to a safer space is still possible, but it requires deliberate choices: enforcing climate pledges, reforming food systems, ending fossil fuel subsidies, and changing consumption among the wealthiest groups. The task has become harder, but it has not become impossible.

Inertia, Limits, and Irreversibilities

Systems That Resist Repair

The planetary boundary studies make one point unavoidable: even with ambitious action, some Earth systems will take decades to heal, and others may never recover. This is because environmental systems carry inertia. Once destabilized, they do not snap back like a spring.

Climate is the clearest example. Even if global emissions fall to net zero, the carbon already in the atmosphere continues to trap heat. Oceans, which have absorbed much of that heat, will slowly release it back over centuries. This lag means temperatures only decline gradually, even under net-negative emissions. Ice sheets such as Greenland’s and the Arctic sea ice are already showing this: once melting begins, the process sustains itself for centuries. The consequence is rising seas that threaten coastlines, displace millions of people, and force whole cities to either adapt or abandon land to water.

Biodiversity faces an equally stubborn constraint. Extinction is permanent. Once species disappear, ecosystems unravel. Coral reefs show this vividly. When warming waters bleach and kill reefs, it is not only the loss of a beautiful landscape. Reefs provide food and income for hundreds of millions of people, shelter coastlines from storm surges, and support fisheries that feed entire regions. Their loss ripples outward: weaker economies, poorer diets, and greater vulnerability to disasters. Protecting what remains is therefore as important as restoring what is degraded.

Nutrient cycles — nitrogen and phosphorus in particular — also resist quick fixes. Heavy fertilizer use has oversaturated soils and rivers, creating “dead zones” in lakes and coastal waters. These are areas where oxygen levels collapse and fish cannot survive. For communities that depend on fisheries, dead zones mean livelihoods vanish. For ecosystems, it means chains of life — from plankton to predators — are cut. Even with better fertilizer management, the excess chemicals already in the environment will take decades to cycle out.

Where Progress Comes Quickly

Not all processes are this stubborn, some respond quickly to policy. Aerosols, the fine particles released by burning coal and oil, clear from the air within weeks. This means air quality can improve within a single decade. China’s air pollution controls after 2013 show this: particulate matter fell by nearly 40 percent in less than ten years, avoiding millions of premature deaths. Water use is another area where change is visible quickly. Modern irrigation, recycling wastewater, and better allocation can ease freshwater pressures within years, improving both food security and access to clean water.

But other processes are irreversible on human timescales. Ice sheets, once destabilized, continue to melt for centuries. Rising seas will reshape coastlines for generations, no matter what policies we adopt now. The only question is whether the rise will be measured in manageable centimetres or in metres that redraw the world map.

The Stakes

None of this means that action is futile. Success must be defined realistically, the goal is not to return Earth to a pristine past, but to stabilize its systems at levels where societies can continue to thrive. The science shows that much of what we need to do is clear. Cut fossil fuel subsidies, enforce climate pledges, reform food systems, waste less, and reduce the outsized consumption of the wealthy. These are practical steps, not mysteries, and the obstacles are political and economic, not technical.

What is at stake is not abstract. Rising seas mean the loss of homes and cities. Collapsing biodiversity means the collapse of fisheries, food supplies, and natural protections against storms and floods. Dead zones in rivers and oceans mean livelihoods erased. Climate change is not a far-off crisis, but a direct threat to food on the table, water in the glass, and roofs over people’s heads.

Yet we continue to act as if nature’s value must be proven in financial terms before it counts. We treat forests as valuable only when they can be logged, soils only when they can grow crops for profit, air only when it’s pollution begins to hurt productivity. Meanwhile, we elevate GDP growth as if it were more real than the ecosystems that make life possible.

There is still time to change course. But it requires abandoning the illusion that markets alone will deliver salvation. A stable biosphere is not a luxury good to be earned. It is the foundation of every economy, every society, and every future. Forget that, and we risk a future where humanity needs to eat diamonds, while every last tree is dead.

Maya Nitasha Pirzada is deeply interested in the history, law, sociology, and politics of South Asia and has travelled extensively across Pakistan. She is currently pursuing her studies in Maryland, United States.