For Pakistan’s economy, currently going through yet another troubled period, it has always been a tale of two deficits – the Current Account (CA) deficit and the Fiscal deficit. The unmanageable CA deficit sent Pakistan back for the 22nd time to the IMF in 2019, while the perennial struggle to control the fiscal deficit continues on the domestic front.

In broad terms, the CA deficit is the shortfall in our foreign exchange (FX) earnings – we earn FX primarily through exports and inward remittances from overseas Pakistanis, and we pay out FX for our imports and debt servicing. The fiscal deficit is the shortfall between government revenues and expenditures. Both these deficits have to be financed in some manner, and when they become large and unmanageable, they have repercussions for the overall macroeconomic situation.

The mandate for the new team was to arrest the decline in the economy on a war footing. The buzz word for the new team was macroeconomic stabilization – the house needed to be brought in order before any positive initiatives could be taken.

The PTI government inherited an economy in a dire position, close to defaulting on external obligations, when it came to power in August 2018. The warning signals had been flashing even during the later stages of the PMLN government. The caretaker government, too, during its tenure from June 2018 to August 2018, kept emphasizing the need for clear and decisive measures from the incoming new government.

Nevertheless, precious time was lost in the early months of the PTI government, a period marked by dithering and confusion. The Prime Minister made fundamental changes to his key economic team at the end of the first quarter of 2019. Dr. Abdul Hafeez Sheikh was appointed as the Advisor on Finance to the PM in April 2019, and Dr. Reza Baqir was appointed the Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan in May 2019.

Read more: Restructuring Pakistan’s budget to cope revenue shortfall

The mandate for the new team was to arrest the decline in the economy on a war footing. The buzz word for the new team was macroeconomic stabilization – the house needed to be brought in order before any positive initiatives could be taken.

What did PTI inherit?

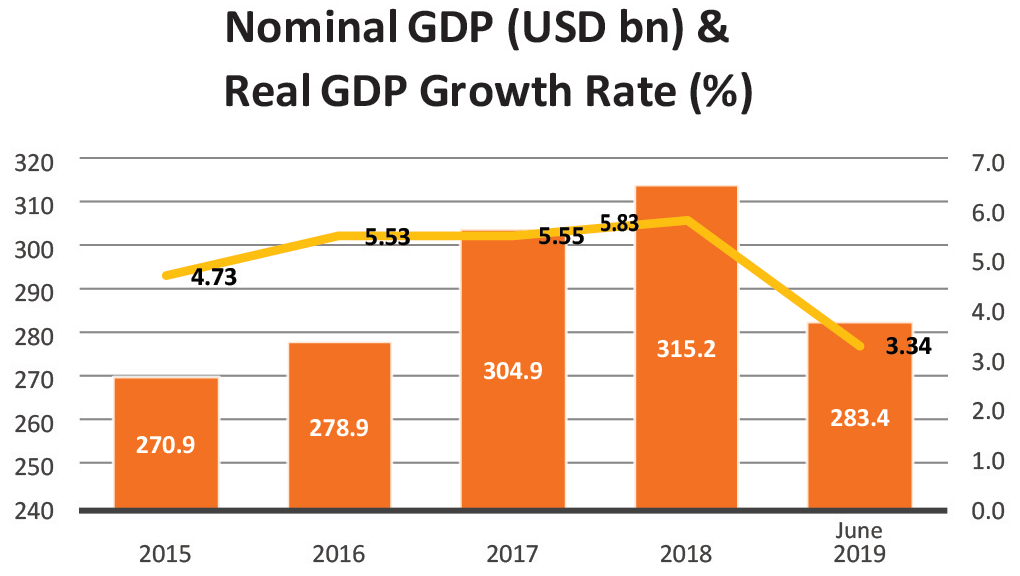

To get a good sense of where the economy was at the start of the PTI government tenure, let us recap a few of the major economic indicators as on June 30, 2018. This date is, of course, the end of the financial year 2017-18 (FY2018) for the government accounts and, therefore, sums up the economic situation for the full year.

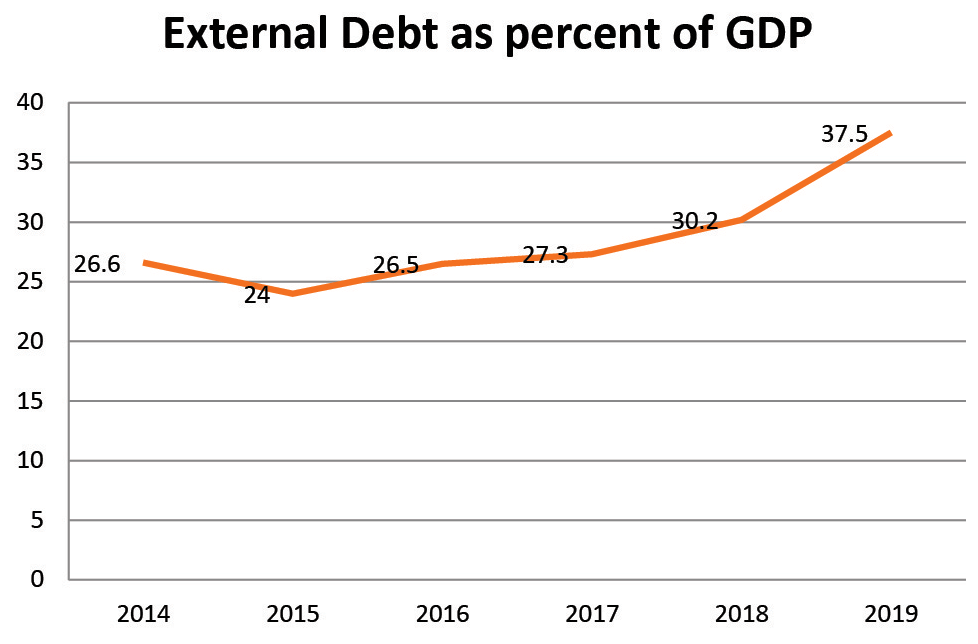

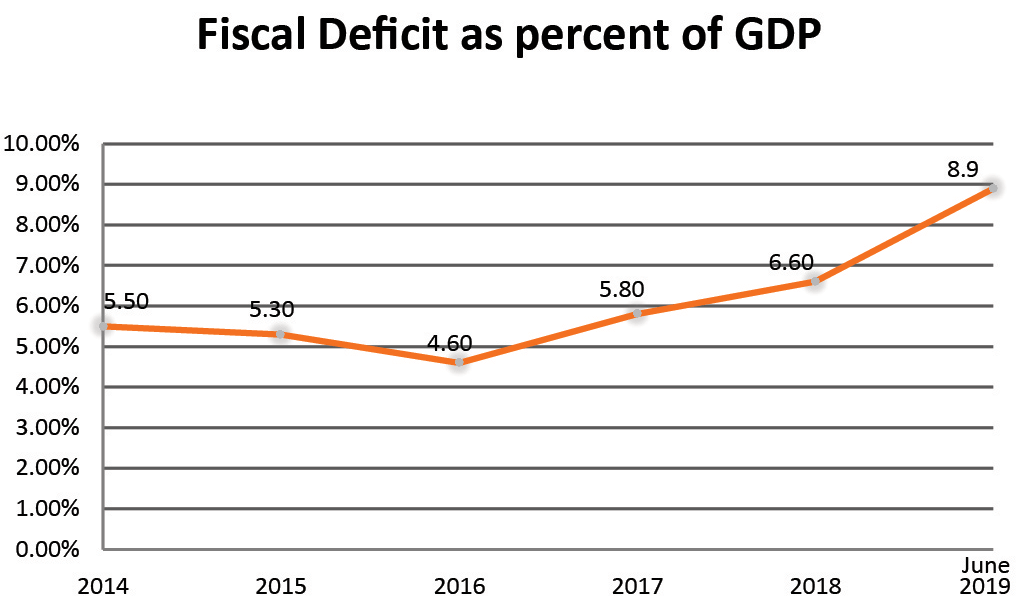

It is also a natural break in terms of change of government as the general elections were held in July 2018, and the PTI government took office in August 2018. The CA deficit stood at $19.9bn in FY2018, which was equivalent to 5.8% of GDP. The fiscal deficit stood at Rs2.26tr or 6.6% of the GDP.

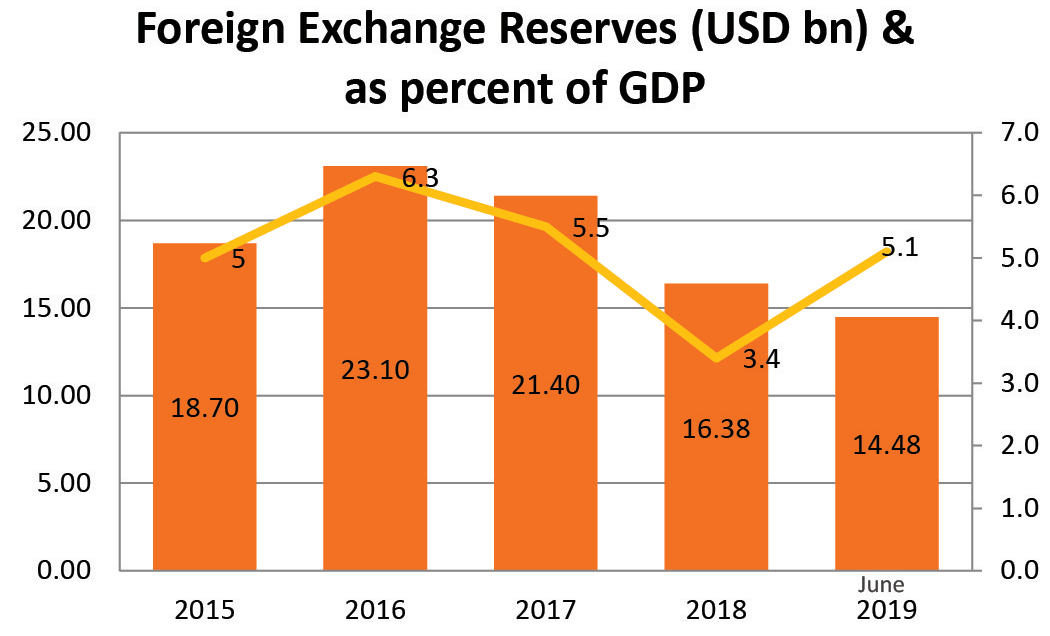

The FX reserves stood at $9.8bn, down from a peak of $18.1bn in FY2016 and the equivalent of fewer than two months of import cover. The priority for the economic team had to be the CA deficit. The persistent, large deficits had had the effect of running down the FX reserves to critical levels. This meant that the country’s ability to adequately serve its essential import requirements was threatened.

An overvalued rupee was perhaps the most egregious economic legacy of Mr. Ishaq Dar as finance minister in the PML-N government.

Also, at stake was the country’s ability to continue servicing its external debt obligations, including payment of principal and interest. Any default on the external debt would have had unimaginable consequences. To control the CA deficit, the exchange rate needed to be brought to a realistic level. An overvalued rupee was perhaps the most egregious economic legacy of Mr. Ishaq Dar as finance minister in the PML-N government.

An overvalued currency meant a double whammy – imported goods were cheaper and flooded into the country, while our exports became uncompetitive and lost existing market share in competitive global markets. So, the CA deficit kept on widening. To compound matters, precious FX reserves were squandered in defending this unrealistic exchange rate.

Read more: Budget 2018-19: Impervious to economic challenges

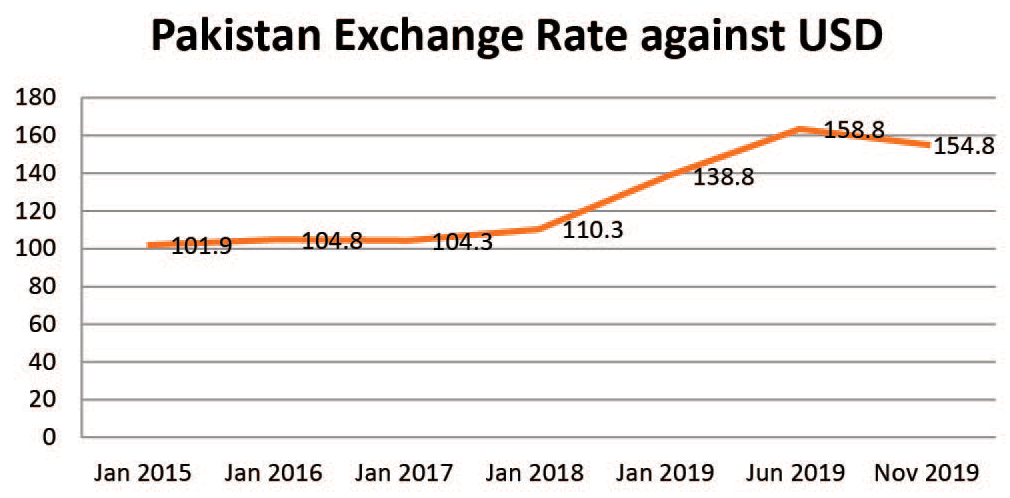

The PTI government carried out the exchange rate adjustment process in several tranches. A standard measure of a currency’s correct value is the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER), a weighted average of the currency’s value against a basket of the currencies of its major trading partners.

A REER of above 100 indicates overvaluation. In August 2018, when the new government came in, the average $/PKR rate was 124 (REER 106). By July 2019, the average rate had hit Rs159 (REER 90). The adjustment process was virtually over as the exchange rate had stabilized and was being determined mainly by market forces. The question is: has the exchange rate adjustment had the desired effects? Let us again look at some numbers to gauge the progress.

What do numbers say?

The CA deficit declined from the above $19.9 bn in FY18 to $13.5bn in FY19. In the current financial year, we see continuing progress. The latest quarterly numbers of FY20 show the CA deficit at $1.5bn, compared to $4.3 bn in the first quarter of FY19. A more in-depth look into the CA deficit shows that imports have declined appreciably.

The export picture is more nuanced as exports have been on a mild upward trend since hitting a low in August 2017. The export volumes were up 12% during FY 2018-19. The export values have not gone up to the same extent, as a slowing global economy has meant that commodity prices are relatively soft.

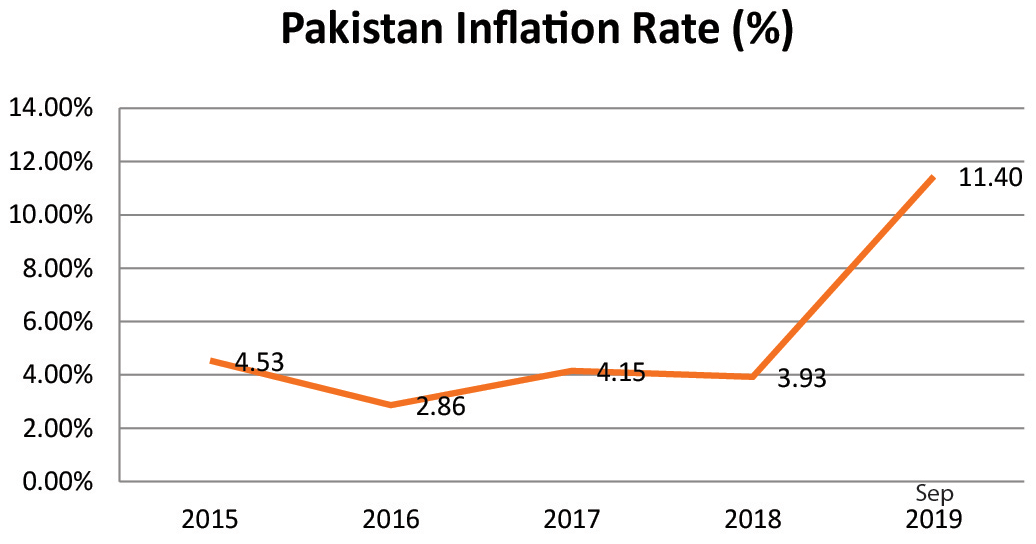

Volumetric growth, however, does show that market share is being gained, so it is a very positive sign. While the exchange rate adjustment was inevitable, it had its downside in the significant surge in inflation in the domestic economy as imported goods became more expensive in rupee terms. Some of our imports are essential and so relatively price-insensitive, none more so than petroleum and oil products.

There finally seems to be a serious government focus on exports. It is one of the sad wonders of Pakistan’s economic policy that when there were shining examples, pan Asia of exports led wonders of economic development, we missed the boat completely for decades.

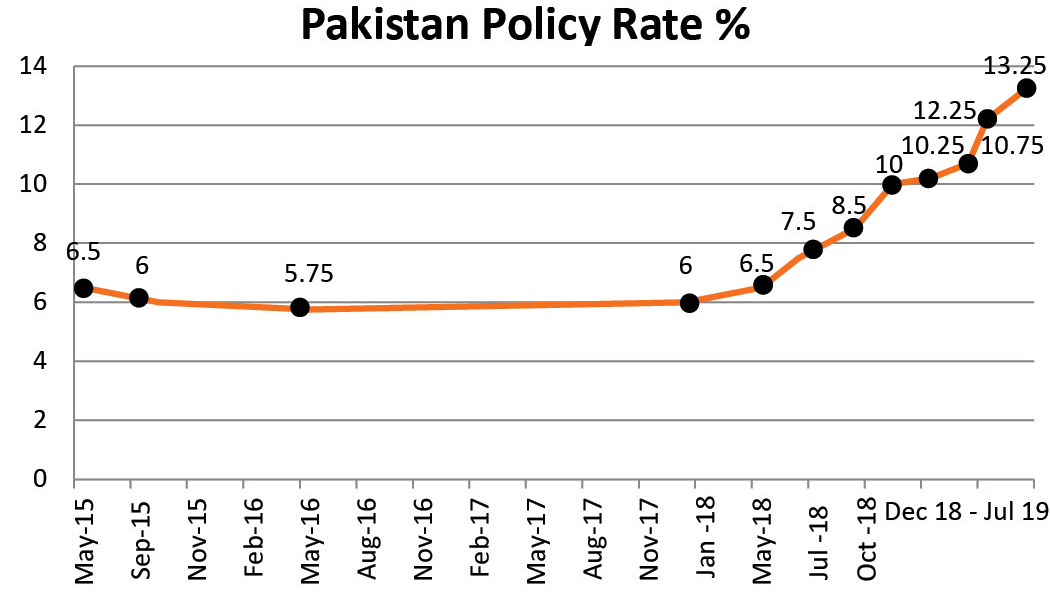

Oil prices, in turn, affect almost all other costs. The orthodox monetary cure for curbing inflation is higher interest rates. The SBP raised the policy rate from 6.5% to 7.5% in July 2018 and, all the way, up to 13.25% in July 2019, where it now stands. Two rationales are traditionally given for higher rates.

The first is that the real interest rates have to be positive (i.e., higher than the inflation rate) in order not to curb savings and distort other economic activity. Secondly, it is considered that one of the causes of inflation is excessive demand in the economy, so higher interest rates (i.e., cost of borrowing) dampen excessive demand. Some have argued with this policy measure.

They maintain that the nature of inflation in Pakistan is mostly costpush and not demand-pull. Interest rates do not significantly affect aggregate demand because borrowing from the formal banking sector (which is interest-rate sensitive) is relatively less critical at the consumer level. There is some validity to that viewpoint.

Read more: Pakistan on its way to becoming a cashless economy

The actual position is that there is some element of cost-push and some element of demand-pull, and government policies have sought to attack it on both fronts. While inflationary pressures remain in the economy, there is a building consensus that inflation has peaked. The average inflation numbers that the SBP looks at will continue to be high for some more months, but the year-on-year inflation numbers should show the slowing inflationary trends.

The one wild card will be international oil prices, that have a real and critical impact on our inflation numbers. That consensus on slowing inflation is being reflected in the interest rate trends; as observed above, the two move in tandem. Government bond yields have come down firmly in the market, as seen in the last few bond auctions.

There is now a yield inversion where short-term rates are higher than long-term rates showing that the market expects lower inflation and thus lower interest rates in the future. In the latest government bond auction on October 30, 2019, the yields for three years, five years, and ten years, the Permanent Interest Bearing Shares (PIBs) went down from between 0.9% to 1.15%.

The yield curve shows that the three-month government paper yields 13.1%, while the ten-year yield is 11.4%. The policy rate, set by the SBP periodically, remains unchanged at 13.25%. It is arguable that, while this remains an important rate, the actual market rates (which, as seen above, are declining) are more crucial.

Nonetheless, the messaging from the SBP seems to be that we should not expect too much by way of a policy rate cut, at best perhaps a token reduction in the next Monetary Policy Committee meeting due in November. The SBP wants to err on the side of caution and try to smother inflation expectations for good.

The downside of this policy could be that any economic turnaround will be unduly suppressed or delayed. The Fiscal deficit was always going to be a tougher nut to crack than the CA deficit. While there has been an improvement in the latter as seen above, signs of significant progress are not readily visible on the former.

Read more: Pakistan’s Economy may become worse under FATF’s grey list

The FY19 debt stood at Rs3.445tr or 8.9% of GDP, possibly the highest ever, and significantly worse than the FY18 figure of Rs2.24tr or 6.6% of GDP that the PTI government inherited. The target for FY20 is 7.1% as per agreement with the IMF.

Tax collection targets missed, revenue shortfall grows

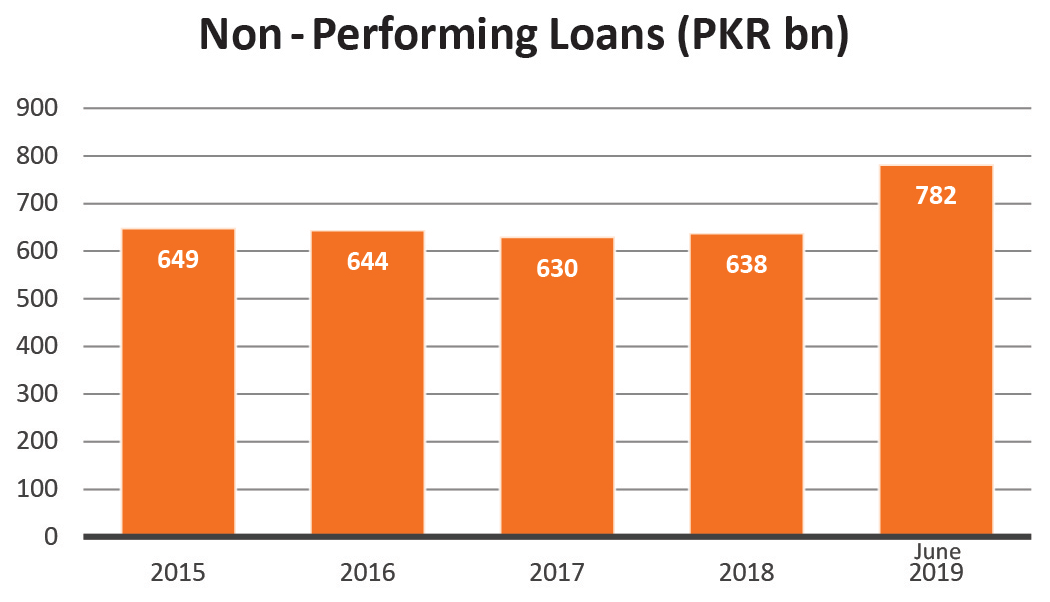

On the all-important revenue side, tax collection targets are being missed. It is, partially, because goals were too high and unrealistic, as expressed by most observers at the time of the presentation of the FY20 budget. There is also the expected and continuing resistance from the taxpayers.

Besides, there are perennial questions as to the execution capacity of the tax collection machinery, which is generally regarded as inefficient and corrupt. The other side of the fiscal deficit is, of course, the expenditure side. The fact is that there is not much room for cutting government expenditure.

After accounting for provincial allocations, debt servicing, defense, and administrative expenditure, the federal government is left with minimal discretionary spending. The burden falls typically on the PSDP, the public sector development program, which in turn hurts GDP growth and employment.

The difficult war on the fiscal deficit has to be fought and won step by step. It will be an attritional war. If it is accepted that the tax to GDP ratio in Pakistan is low – and it is one of the lowest in the world – then the government must stand firm in the face of internal bureaucratic inertia and external stakeholder resistance and maintain the course.

Read more: Why Banks are not doing enough in Pakistan?

So far, the government seems to be directionally correct, even if the results are not uniquely different. One of the encouraging signs is that the government announced that it had run a primary surplus in the first quarter of FY20.

Structural reforms and growth pain

Of course, bringing the various macroeconomic indicators in line is not an end in itself. The eventual aim has to be the betterment of the populace through economic growth, employment, and a rise in per capita income. For this to happen, and to be sustained, various structural reforms have to be made.

Structural reforms, like any significant change, bring about a degree of pain. The misfortune of Pakistan and the reason for our periodic economic crises and repeated recourse to the IMF has been that while governments have managed to bring economic variables in line for short periods, usually under IMF tutelage, the necessary follow up reforms have not happened.

We have repeatedly kicked the proverbial can down the road. The success, or otherwise, of the PTI government, will have to be judged on its ability to not only bring short-term stability but to undertake the problematic reforms which will make economic progress sustainable. Some outlines of the possible directions of the current government are evident now.

The new thinking at SBP on exchange-rate-management thinking seems to be firmly established now and has been clearly communicated to the financial markets. While going forward, market forces will determine the exchange rate with possible SBP interventions to smooth out excessive volatility.

Read more: Imran and the IMF: Pakistan’s bailout dilemma

While only fools predict exchange rates, a helpful way of thinking about the future course of the Pakistani rupee would be that it will depreciate overtime against the dollar-driven by the inflation differential between the US dollar and the Pakistan rupee. On the external front, bringing the CA deficit under control was a first and necessary step. There is a need to move beyond it. The FX reserves need to be built up.

It is a requirement of the IMF program and is necessary to reduce the overall vulnerability of the economy. While the decline in reserves has been arrested, the FX reserves are not growing and continue to hover at around $7bn to $8bn levels. The government will likely issue Bonds/Sukuks in the international markets very soon that will be long-term money that will shore up the reserves and provide some breathing room.

The government also needs to plan ahead for a period of higher economic growth, perhaps by FY 2021, when it is likely that import demand will go up, putting pressure once again on the CA deficit. There finally seems to be a serious government focus on exports. It is one of the sad wonders of Pakistan’s economic policy that when there were shining examples, pan Asia of exports led wonders of economic development, we missed the boat completely for decades.

The exports will, in the foreseeable future, come from traditional areas like textiles and possibly the value-added food sector. Interestingly, the latest SBP review released in October 2019 has called for a review of the economic policies that have resulted in a growing service sector and manufacturing industry in relative decline.

Read more: Imran Khan: Pakistan will soon emerge as the leading economy in the region

According to the SBP, the only way to sustained export performance is through a vibrant manufacturing sector. There are still areas of uncertainty. CPEC is one such area. There is a slowdown in this significant initiative, which was heralded as a vital game-changer for Pakistan. Part of this slowdown is just a changing of gears as it moves from the first stage to the next.

Nevertheless, the government must give more clarity on the timelines and progress on the next stages of this project, e.g., the setting up of the Special Economic Zones and the Chinese private sector investment. GDP growth is expected to be around 2.5% for FY20.

The likelihood is that a higher growth trajectory cannot be established before FY21, once the current issues work themselves out entirely, some of the results of the ongoing reforms will start to kick in. One of the disappointments of the PTI government on the economic front has been its exceptionally poor communication. The government, while loudly proclaiming its commitment to reform, has singularly failed to create a constituency for change.

It is generally recognized now that success is also a game of successful narratives, in economics and all other areas as well. The government needs to put serious thought and resources into designing and successfully communicating this narrative to create the necessary buy-in and political will for the complicated process ahead.

Samir Ahmed is a financial sector professional with more than 30 years of experience in Capital Markets, Investment Banking and Financial Regulation, domestically and internationally. He is a graduate of the University of Chicago and London Business School. He tweets @samirahmed14.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.